In our previous installment, Ruth, Claire and Nigel talked about some of their favourite objects and why they enjoyed working on them so much. This time our conservators attempt to answer a rather complex question...

ALEX: So what is the difference between conservation and restoration?

CLAIRE: I think good restoration has to come with a conservation approach. They aren’t mutually exclusive.

ALEX: In what way?

CLAIRE: Restoration can be seen as a dirty word; conservators are expected almost to disapprove. But actually we don’t, restoration is a fundamental part of conservation and of keeping an object alive or accessible, from engine parts to replacement handles. But you create the new parts ethically, you only create what you have evidence for, are honest about it, and use the correct materials.

NIGEL: Conservation is about documentation, preserving originality, ethics etc.

CLAIRE: Restoration is essentially putting back something that was lost, but you have to have the evidence and you have to put it back sympathetically and only if you can justify it against our conservation ethical code. But I see it totally as part of conservation and not the other way round!

RUTH: What Claire said!

CLAIRE: Restoration in a vacuum without any conservation context could potentially cause damage.

NIGEL: Some of our collections have been subject to this in the past.

CLAIRE: There can also be a fine line between what is considered ethical or not. So discussions between a conservator/restorer and client or curator are really important to see where the justification falls. What the object requires for preservation and what the client wants from that object can be very different. In the commercial restoration world, the client’s requirements can be seen as justification for taking things further than we might think was ‘ethical’ in the museum world. While you can have the conversation with the client about why full restoration might not be a great idea - the loss of history and authenticity, and possibly evidence for use - ultimately if they really want their object to look as it was when they were a child, and bring back those memories that are important to them, then they have the right to ask for that. If you felt uncomfortable as a conservator you could refuse the job, but in reality I think you’d talk it through and find a balance you were both happy with.

ALEX: Have you had much experience of this?

RUTH: I have done [a] bit. The client thought I was a restorer and wasn’t pleased he could see the repair! Like Claire said it is usually based around the client’s expectations.

NIGEL: It was very different when I worked building vintage cars. The client totally steered the direction of the project.

CLAIRE: Usually once you’ve explained the ethics and the outcome and you know they understand, they’re happy.

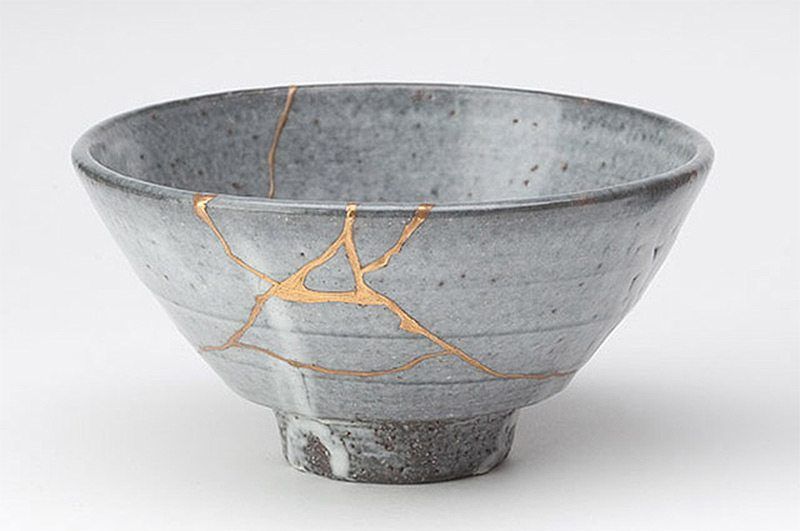

ALEX: It’s got me thinking about the Japanese practice of repairing pottery with gold so you can see the repair[1].

RUTH: Love that technique!

NIGEL: So do I. Most of the work [I do] is hidden. You need to always be honest and transparent. [That’s] why documentation is so important.

ALEX: Have there been changes over time in how to conserve objects in terms of the visibility of that repair?

CLAIRE: Yes, conservation has been subject to fashion in the past.

ALEX: What is the biggest change?

CLAIRE: The change from disguising repairs, for example in pottery, where you might airbrush over the original surface in order to blend it in, and the method I use, where you do a 6 foot invisible, 6 foot visible, and honest, repair. We are better now at writing down what we’ve done.

ALEX: So as Nigel said, documentation is key.

CLAIRE: I think early restorers used to revel in the mystery of what they did, they hid away and enjoyed a slightly enigmatic status … now we share as much as we can!

RUTH: Documentation is so important, particularly when undoing something from a past treatment.

ALEX: This method of not blending the repair links well with the darning work you’ve been doing on the teddies[2]doesn’t it?

RUTH: Yes the rule is very obvious with the teddies and the darning I have been doing.

ALEX: Nigel, is your conservation work on the vehicles as visible in the same way as the teddies?

NIGEL: No most of the work is hidden inside the vehicle.

Next time we have questions from colleagues at Hampshire Cultural Trust for the team to answer.

[1] This is known as Kintsugi literally translates to “golden joinery” and is a longstanding tradition in Japan. Rather than hide the repair to a broken ceramic vessel, gold lacquer is used to bind the pieces together, adding to the story of the object.

[2] Mr Simpson’s teddies is a collection of teddy bears bequeathed to Hampshire Cultural Trust by an avid collector. Ruth has written about working on these teddies as part of Culture on Call.

If you have enjoyed Culture on Call and you are able to make a donation, any support you can give will help us keep people connected.