In the first part in our four part series for Winchester Green Week 2020, we introduce Hampshire-born Gilbert White, an 18th century pioneer of the study of animals and plants.

"It is easy to imagine him, this very first of English nature writers, the most sober and modest, yet happiest of men."

Flora Thompson

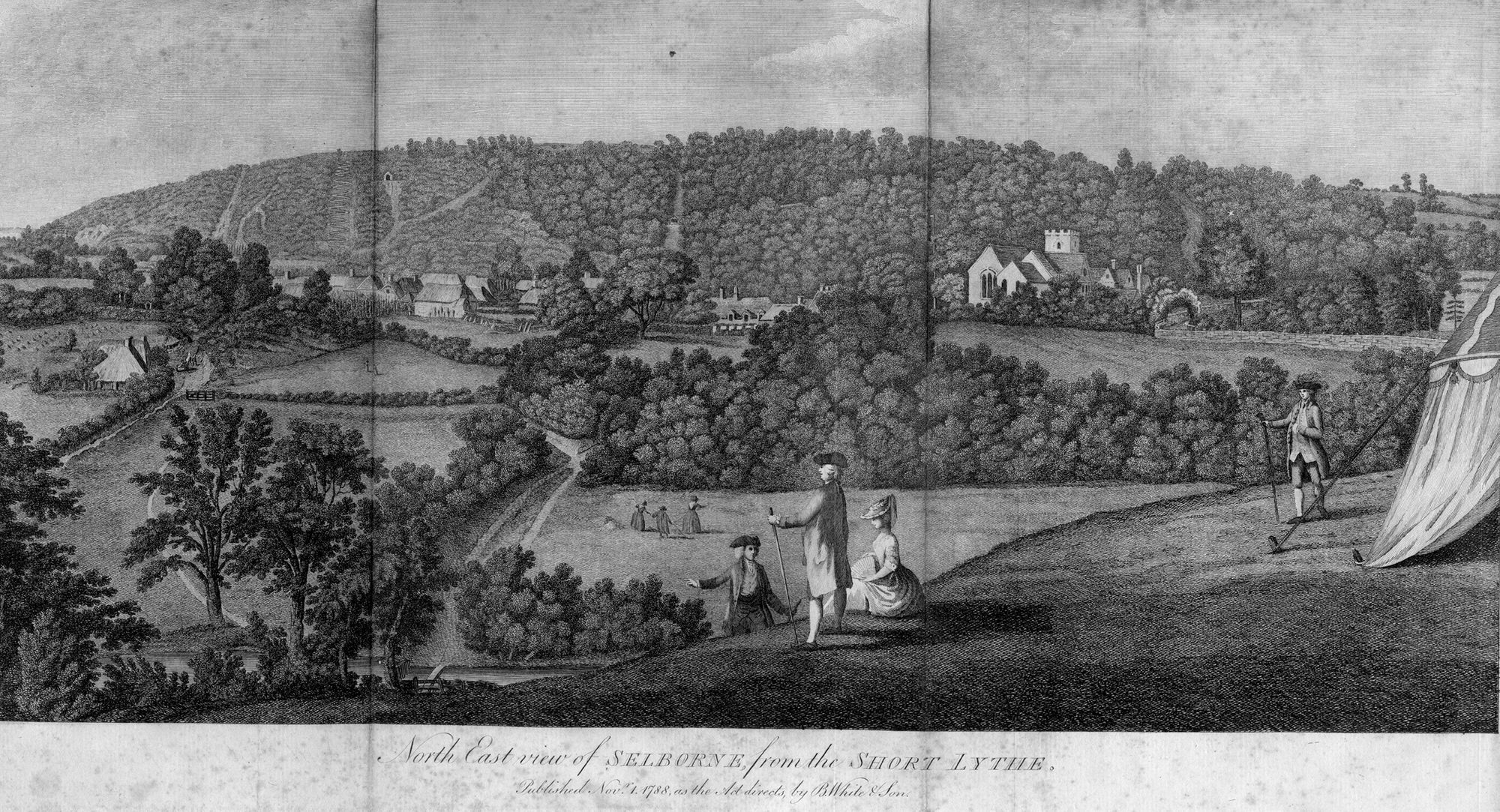

Selborne is a village nestling in the heart of the Hampshire countryside. The village outwardly appears to have changed little since the late 17th century, when the observations of the local curate transformed our understanding of the natural world and the ecology of the planet.

Gilbert White was born in Selborne on 18 July 1720. In 1728, the family moved into the ‘The Wakes’, the house that White was to call home for the rest of his life. His grandfather was the vicar of Selborne and Gilbert also chose a career in the church. He received his degree from Oriel College, Oxford in 1743 and was ordained in 1749.

On the death of his father in 1758, he moved back to the family home at The Wakes, where he spent the next 35 years devoted to scientific, evidence-based study and recording of the natural world. His obvious empathy with the lives of the creatures he observed, expressed in the humour and warmth of his writing, was revolutionary and has earned him the title of England’s first ecologist.

A new kind of zoology

White is best known for his book The Natural History and Antiquities of Selborne, published in 1789. This takes the form of a series of letters to zoologist Thomas Pennant, in which he summarised the earliest and latest dates for the emergence of plant and animal species at Selborne over a 25-year period. One of the earliest examples of modern phenology, it has never been out of print.

Phenology is the study of periodic plant and animal life cycles and how these are influenced by seasonal and yearly variations in climate, as well as changes in habitat. White used his ‘Naturalist’s Journal’ to record temperature, pressure, wind, precipitation and weather, as well as ‘Tree first in leaf’, ‘Plants first in flower’ and ‘Birds and Insects first appear, or disappear’ along with many other observations.

Recent analyses of these records, together with studies from the first half of the last century and the present day, have identified changes in plant life cycles that can broadly be explained by a trend towards warmer temperatures. White has often been dismissed as a ‘country writer’, yet his pioneering fieldwork is now recognised as contributing to our understanding of a changing climate, with global implications.

If you have enjoyed Culture on Call and you are able to make a donation, any support you can give will help us keep people connected.