With Hampshire Cultural Trust Conservator Claire Woodhead

In August 2019, the trust was able to acquire the Oakley hoard, an assemblage consisting of a copper alloy and wood tankard, another copper alloy vessel, some iron implements and a ceramic vessel. The items were discovered in association with a Late Iron Age burial at Oakley, near Basingstoke, in January 2017. Conservation of the Oakley tankard has already been completed (an account of the work can be read in Hampshire Field Club and Archaeological Society Newsletter, No. 73, Spring 2020).

For this first instalment in a short series of posts for the Festival of Archaeology, we follow the Oakley ceramic vessel into the conservation lab as work begins.

The Oakley vessel – Part 1: Stabilisation

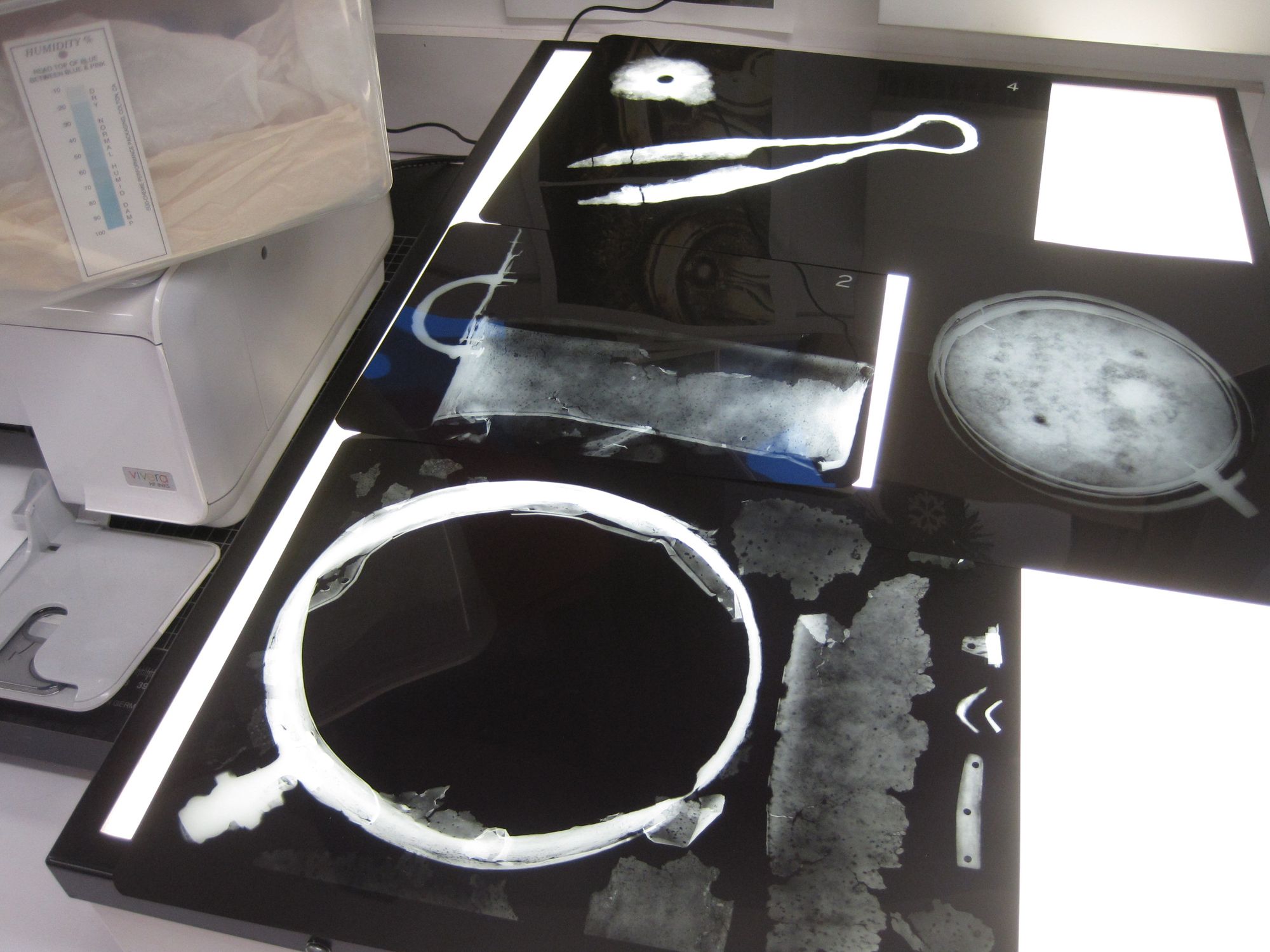

Received into the lab at the end of last year was a ceramic vessel, part of the Oakley hoard. It was lifted from the field partially intact with soil fill still in place - crucial for retaining as much of the pot and associated evidence as possible. The first step was to x-ray the vessel, which can provide a sort of road map for removing the soil fill, or ‘micro-excavation’, in the lab. The x-ray image showed no obvious artefacts of metallic composition, but since organic materials and mineralised metals tend not to show up, caution will still be needed when the time comes to micro-excavate. Before that is possible, the vessel must be stabilised so that it is strong enough to withstand the loss of the soil fill, which is currently acting as an internal support.

Although the pot still retains a structure fairly close to its original shape, it has broken into fragments, particularly around the top half. To avoid having a heap of potsherds at the end, the pot needs to be stabilised before it is emptied. The aim is to be able to retain the strange, crushed and distorted form of the pot, which in itself is part of the story, telling of thousands of years underground.

Thick soil is gently removed from the outer surface, to reveal where the breaks are and to see the extent of remaining pot. The soil is very hard, so is softened first with a little deionised water, before being gently detached with wooden hand tools. Some pot fragments at this point become detached, so their positions are noted for reattachment if possible. Then, a thin, penetrating consolidant is introduced at the cracks, to hold the fragments together during excavation. Applied by a tiny brush, the consolidant is drawn into the porous material, until it is no longer being soaked up.

Structures are generally at their weakest during consolidation, so the exterior of the pot must be supported during the process with cotton tying tape and wedges of inert foam. While the consolidant sets, some stretchy (new – and kept in the cupboard for just such emergencies) nylon tights are even pressed into service.

In the next instalment, micro-excavation commences!

If you have enjoyed Culture on Call and you are able to make a donation, any support you can give will help us keep people connected.