Part 4

It’s National Insect Week and what better way to celebrate than to draw attention to Hampshire’s own local ecology hero. 2020 is the 300th anniversary of the birth of Gilbert White (1720-1793), a naturalist of international distinction and regarded as the father of ecology. Earlier this year we dedicated a special display to him alongside the incredible insect photography of Levon Biss to highlight his important work.

White was responsible for a number of major discoveries in the natural world and a pioneer in the field of phenology – the study of seasonal phenomena.He started his education in Basingstoke before going to Oriel College, Oxford, after which he followed his grandfather and uncle into the Church in 1749. A keen gardener from his youth, he grew a range of traditional and experimental plants and was the first to grow potatoes in Hampshire at his beloved home in Selborne. It was this enquiring interest in the natural world that initiated his earliest written work, recording what he sowed and reaped, the weather and temperature called Garden Kalendar.

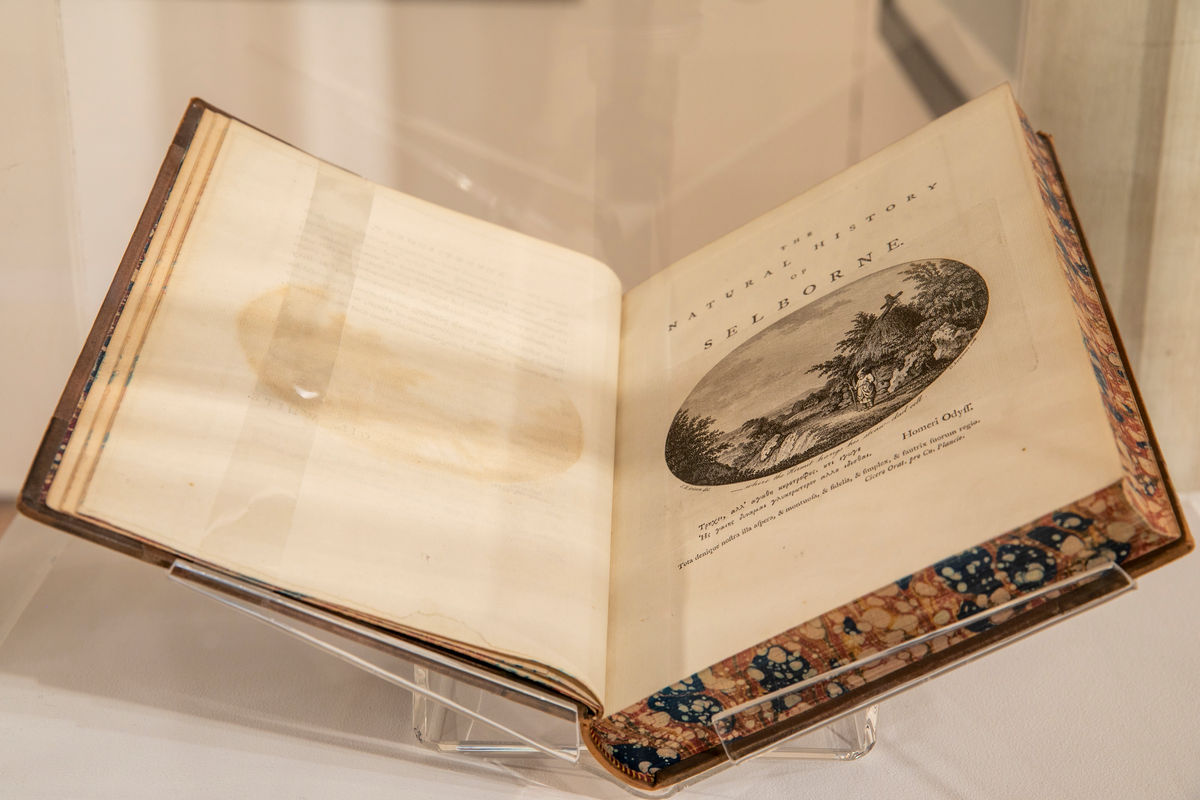

We were fortunate to be able to show a rare first edition of White’s best known publication The Natural History and Antiquities of Selborne (1789) in the exhibition. First published in 1789, just four years before White’s death, this influential literary and scientific work has been in print ever since, with nearly 300 editions published up to 2007. The book is compiled from a mixture of White’s letters to other naturalists - Thomas Pennant and Daines Barrington - and observations of natural history organised systematically by species and group. It reveals his methodology of recording which distinguished him from his peers.

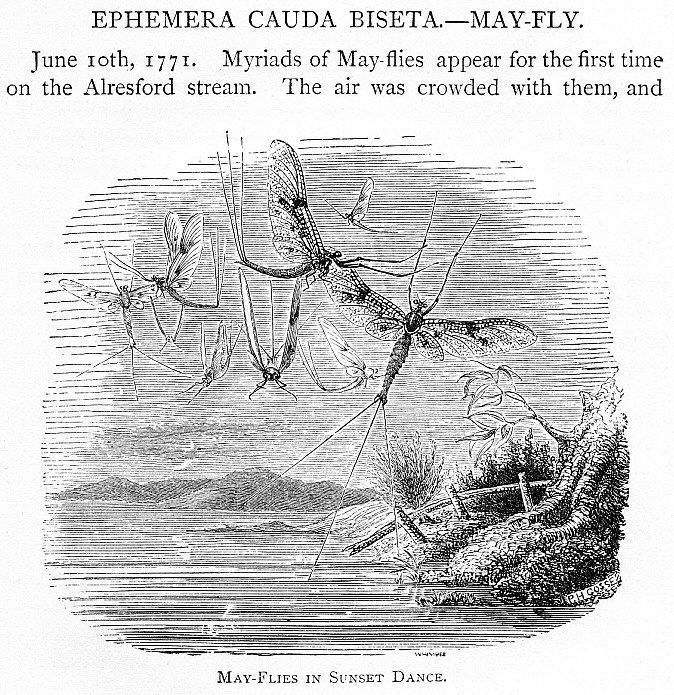

White’s unique approach was to study living insects, birds and animals in their natural habitat, recording everything he saw and heard as well as the environment. He referred to his technique as ‘observing narrowly’. Other 18th century naturalists preferred to carry out examinations of dead specimens and received information from all over the country, however, White closely studied the Hampshire region, enabling him to record changes much as modern researchers do today.

On his insect observations he noted, 'A vast insect appears after it is dusk, flying with a humming noise, and inserting its tongue into the bloom of the honey-suckle; it scarcely settles upon the plants, but feeds on the wing in the manner of humming birds.'

The book was praised by both contemporary critics and the public and has continued to be admired by a range of nineteenth and twentieth century literary figures for its charm and simplicity, providing an insight into pre-industrial England. In the introduction of a 1977 edition of the work, David Attenborough commented that White was, ‘A man in total harmony with his world’.

Generations of ecologists acknowledge the place of Gilbert White in the heritage of natural history. Charles Darwin claimed that he ‘stood on the shoulders’ of White and went on a pilgrimage to Selborne as a young man in 1857, inspiring much of his work. Undoubtedly White’s contribution more than any other has shaped our everyday view of the relations between humans and nature, and we hope this series inspires you to get out over the coming months to observe the flora and fauna on your doorstep a little more closely.

If you have enjoyed Culture on Call and you are able to make a donation, any support you can give will help us keep people connected.