The Royal Oak is one of Winchester’s best-known pubs. Just like the city it calls home, the Royal Oak has a long, interesting and surprising history. One of its more unexpected stories comes from the late-1800s when you could not only buy a pint but also get your pet seen to by the landlord and “dog doctor,” Edward Spary.

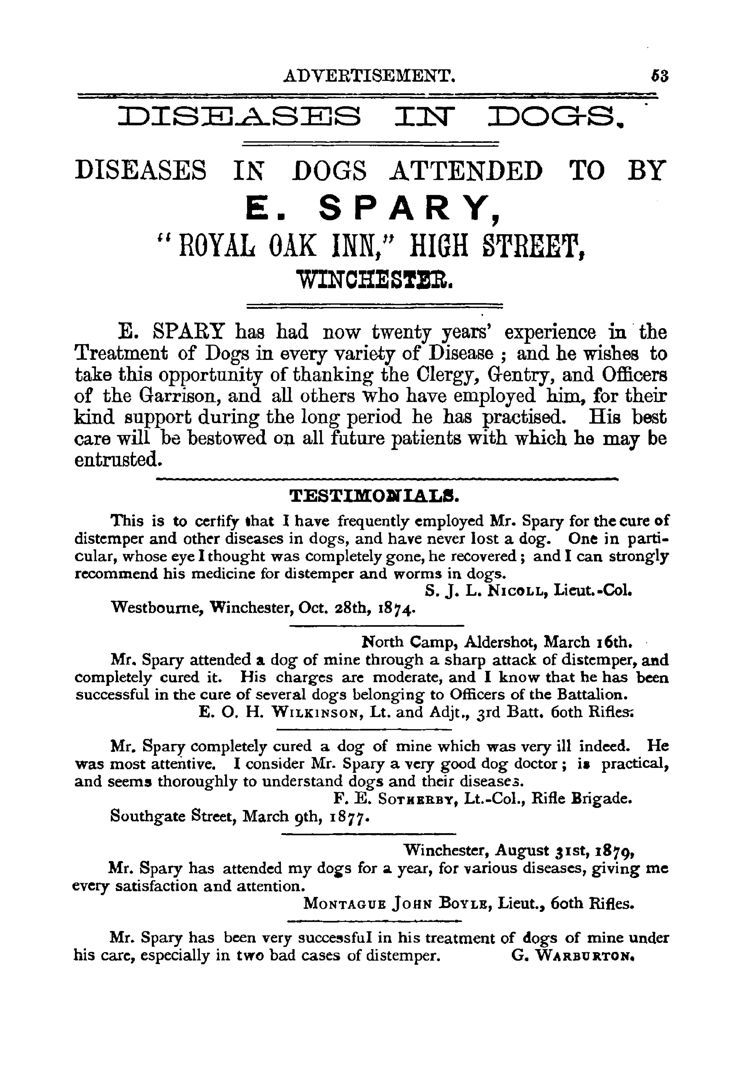

Evidence of Spary’s work as a veterinarian at the Royal Oak comes from an advertisement placed in the 1881 Masters’s Directory of Winchester. The advert declared that Spary had 20 years’ experience in “the treatment of dogs in every variety of disease.” It also announced, in large, bold lettering that anyone seeking help for their pet could find Spary at the pub. Pubs could be many things in the 19th century—they were versatile venues that often offered more than just a quiet pint. It is probably fair to say, though, that a vet practice is relatively unusual!

To understand what was really going on at the Royal Oak in 1881, it is necessary to turn to several sources, including censuses and newspapers. The census return for that year shows that Edward Spary was living at Number 1, Royal Oak Passage. He stated that his profession was a publican, and he lived there along with his wife Mary and their two daughters, Cecily Jane and Mary Ann Maria. He gives no indication of his other work.

In this census, we learn that Spary was forty and originally from New Alresford. He was baptised in the town on 24 June 1840, the fourth child of William and Sarah Spary. It is likely that Spary got his publican inclinations from his parents as, on the 1841 census, we find William and Sarah running The Sun Inn on East Street in New Alresford. They were still running the pub in 1844 and, in 1842, the Hampshire Chronicle commented on the “splendid show of dahlias” that were said to have been in William Spary’s garden—this garden was most likely that of the Sun Inn.

By 1851, however, the pub had been taken over by the Daniels family and would eventually be run by the eldest daughter, Eliza. The Sparys were still living on East Street, but William had turned his hand to horticulture full-time, as he stated that he was a gardener. Within the next ten years, the family had moved to West Street and Edward had followed in his father’s footsteps by becoming a gardener. He retained his love of the outdoors, but his interests by this time must have been moving more towards animals as it would have been around the 1860s that Spary would have first begun to practice as a veterinarian.

It is unclear exactly how he fell into this profession, partly because by 1865 he was a member of the 67th South Hampshire Regiment of Foot, which was based at the Lower Barracks in Winchester. We know this from his eldest daughter’s military birth record. He had married Mary Beaumont, a straw-hat maker who had been living with her widowed mother and siblings on Colebrook Street, two years previously. Therefore, at some point between 1861 and 1863, Spary must have made the journey to Winchester and joined the regiment.

This regimental connection may account for why the testimonials on his 1881 advert were mostly provided by soldiers. Two of those testimonies came from members of the 60th Rifles, who were based at Peninsula Barracks. It is unclear whether Spary was indeed a soldier, but it seems unlikely as, on the 1871 census, he stated that he was “Hants Militia Staff.” It may be that Spary was serving the army in a veterinary capacity as Lieutenant-Colonel Samuel John Luke Nicholl’s testimonial indicates that he utilised Spary’s talents on several occasions in or perhaps prior to 1874.

Spary’s time with the militia came to an end sometime around 1875 as we find him in Kelly’s Directory for that year on the High Street. He had set up shop in Number 3 as a “dog doctor.” In another section of the directory, Spary is titled a “veterinary surgeon” and is shown to be one of three working in Winchester.

By September 1878, Spary had taken up the lease of the Royal Oak. Evidence of this move comes from a Hampshire Independent article that pertained to the tragic death of a young boy from the after effects of a dog bite. We may never know what made Spary move to the Royal Oak. Perhaps he felt nostalgic for a childhood spent in the pub run by his parents, or perhaps it was a bigger premises. The inn boasted a bar parlour, a smoking room, a tap room, a “capital” cellar, four bedrooms, a large yard, two coach houses, and enough stabling for eight horses.

For at least a decade, Spary ran his busy veterinary practice from the Royal Oak. In 1885, Spary found himself in possession of an abandoned foxhound litter and he placed an advertisement in the Hampshire Chronicle for someone to come forward and claim them. Four years previously, he was involved in a case of a “ferocious” retriever dog that bit a young girl. It turned out that several people had been bitten by this dog and Spary was summoned to perform “the agreeable duty of executioner.” Somewhat bizarrely, Spary also features further down in this edition of the paper. In this second section, he was celebrated for catching a “very fine” 5lb 3oz trout in the waters of Winnall. The trout was so remarkable it was put on show by a Jewry Street fishmonger, R. Brown.

Fish remains a strange theme in Spary’s life, perhaps indicating that the Royal Oak was simply a case of him diversifying his business interests. Sometime in early 1888, the family left the Royal Oak and moved to Cavendish Terrace on Hyde Abby Road. Spary moved his practice to this address, too, and made sure to alert his clients with an advertisement in the Hampshire Chronicle in May. By 1889, though, he had begun selling fish and poultry from an address in Fulflood in Winchester, although he maintained his Hyde Abbey address, perhaps suggesting he had gone into business with someone else. The title of the advert is the amusing, “Fish. Fish. Fish.”, suggesting that this is Spary’s focus, but in small text at the bottom of the advert he reminded his readers that “dog doctoring [is] carried on as usual.” In this respect, Spary shows himself to be very much an innovative Victorian man of business.

In 1890, the Good Dog Doctor, Edward Spary, passed away, just two years after his wife, Mary. His was a quietly extraordinary life. 11 years later, a photograph was taken of the Royal Oak Alley. The sign for the pub is visible from behind a streetlamp. It is a calm picture, one which hides the liveliness of men and women on a night out and dogs going for treatment meeting on the pub’s threshold. The next time you go down the alley, spare a thought to Edward Spary and all the cats, dogs, and birds he treated there.

This article has been written by Museum Assistant, Amy-Jane Humphries.