A mainstay of family entertainment for decades, the humble board game can trace its roots back to ancient Egypt. Like all forms of art and entertainment, board games are often a reflection of and commentary on our values as a society. Here, conservator Claire Woodhead takes a look at 1930s game 64 Milestones and what it tells us about the values of the time.

Much of the joy of working in conservation lies in being able to look closely at collections objects, to understand and explore them as the original owners would have done. This is no more apparent than with items such as board games - domestic, humble and predictable, they are often displayed as a closed box or with the board out, but with little chance to see inside and understand the game, or really consider the social commentary hidden behind its concept.

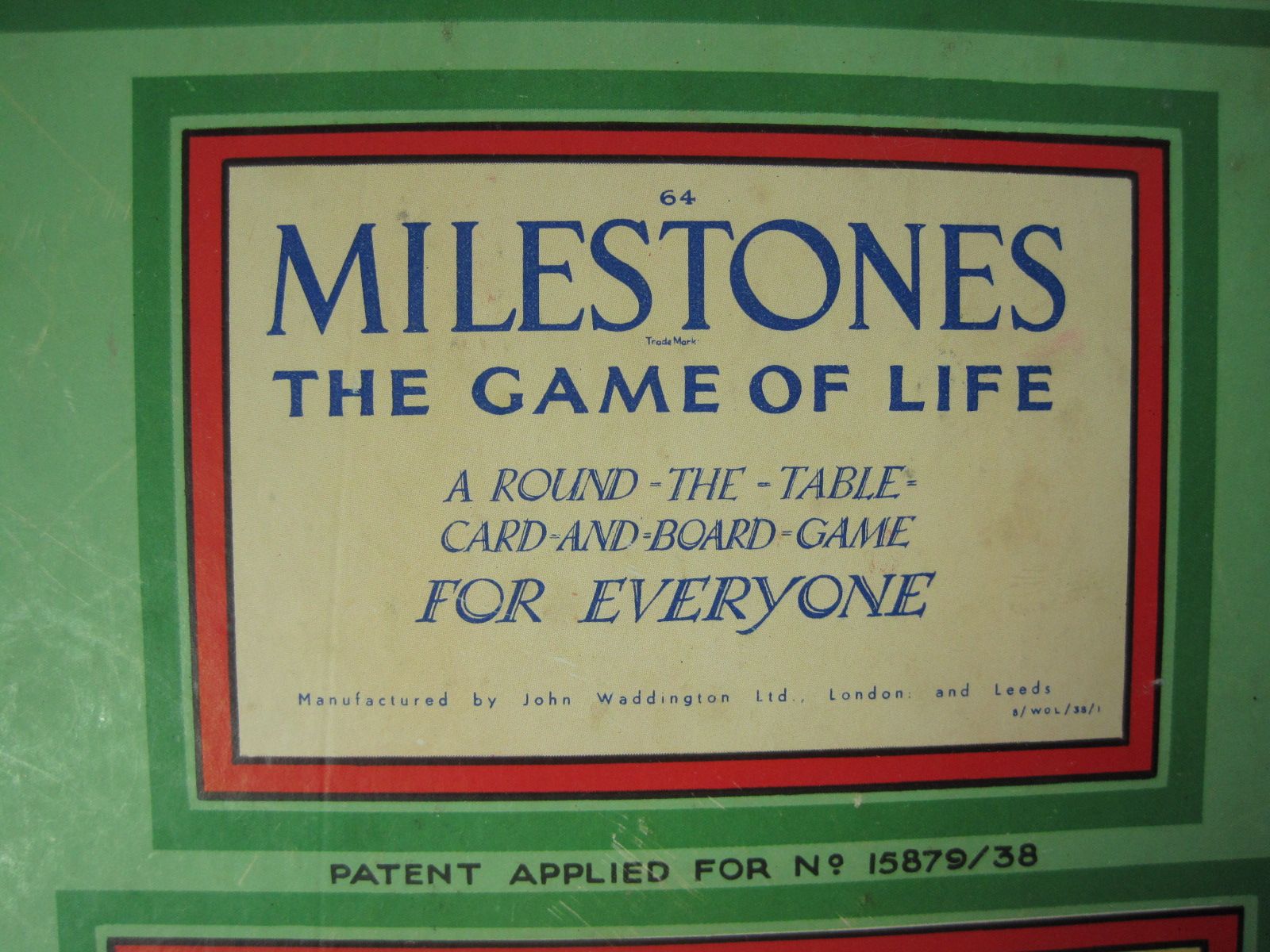

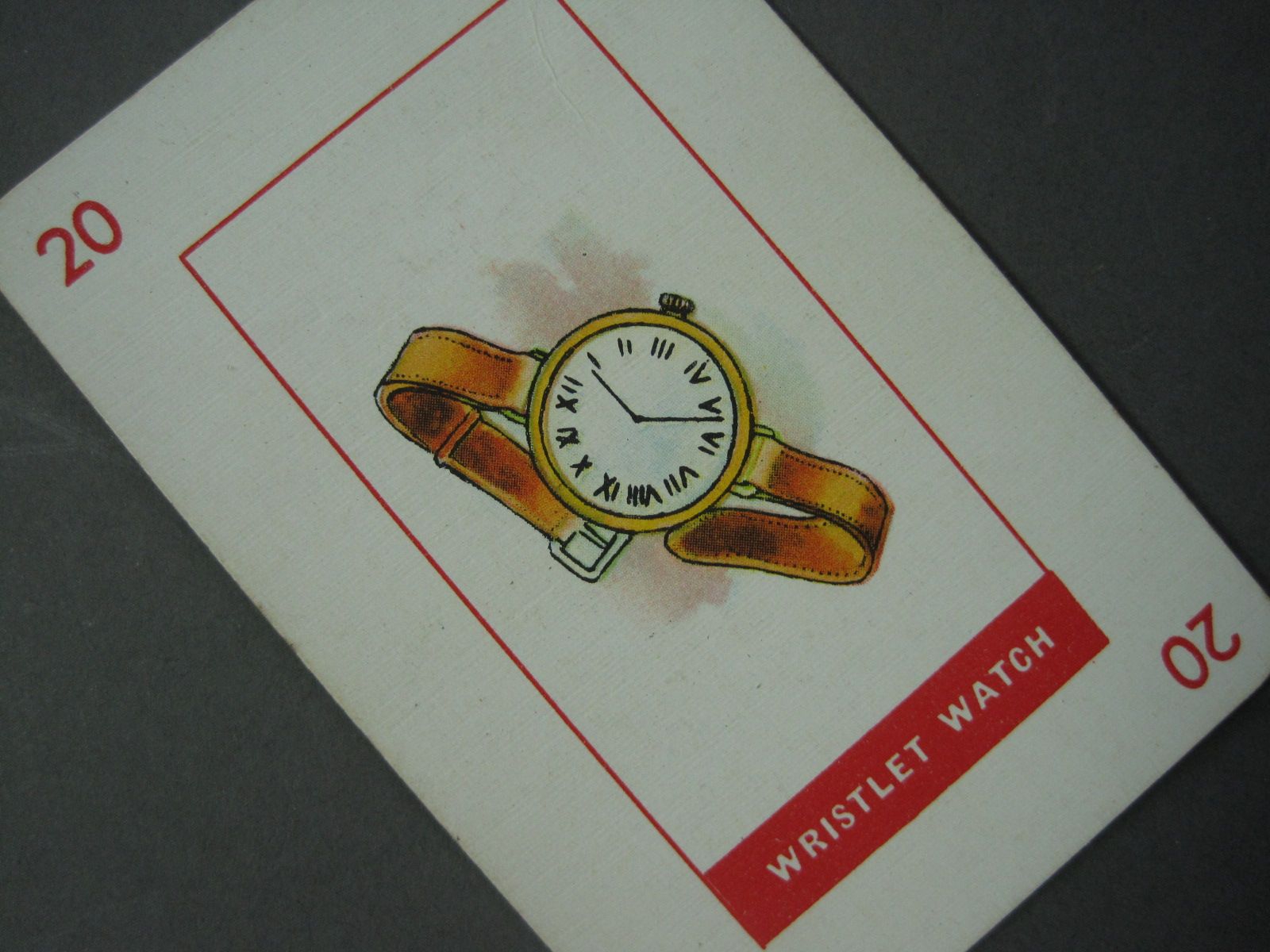

First released in the 1930s, one such game is 64 Milestones or The Game of Life… for Everyone. Immediate interest can be found in the accurate images of 1930s common objects, clothing and early technology portrayed on the board and cards. Equally fascinating is the unintended record of the development of language, for example, ‘wristlet watch’.

On a deeper level, the game presents a picture of society’s highest expectations and aspirations at the time: from birth to retirement at 64, via engagement, marriage, acquiring the required number of comfortable domestic items, luxuries and holidays, the requisite qualifications, employment, promotion and eventually, retreat to an expensive-looking abode at the age of 64. While undoubtedly an idealised construct presented by the game manufacturers, players would have been exposed to these expectations and aspirations and, most likely, have adopted them as reasonable and commendable - if not all ultimately achievable.

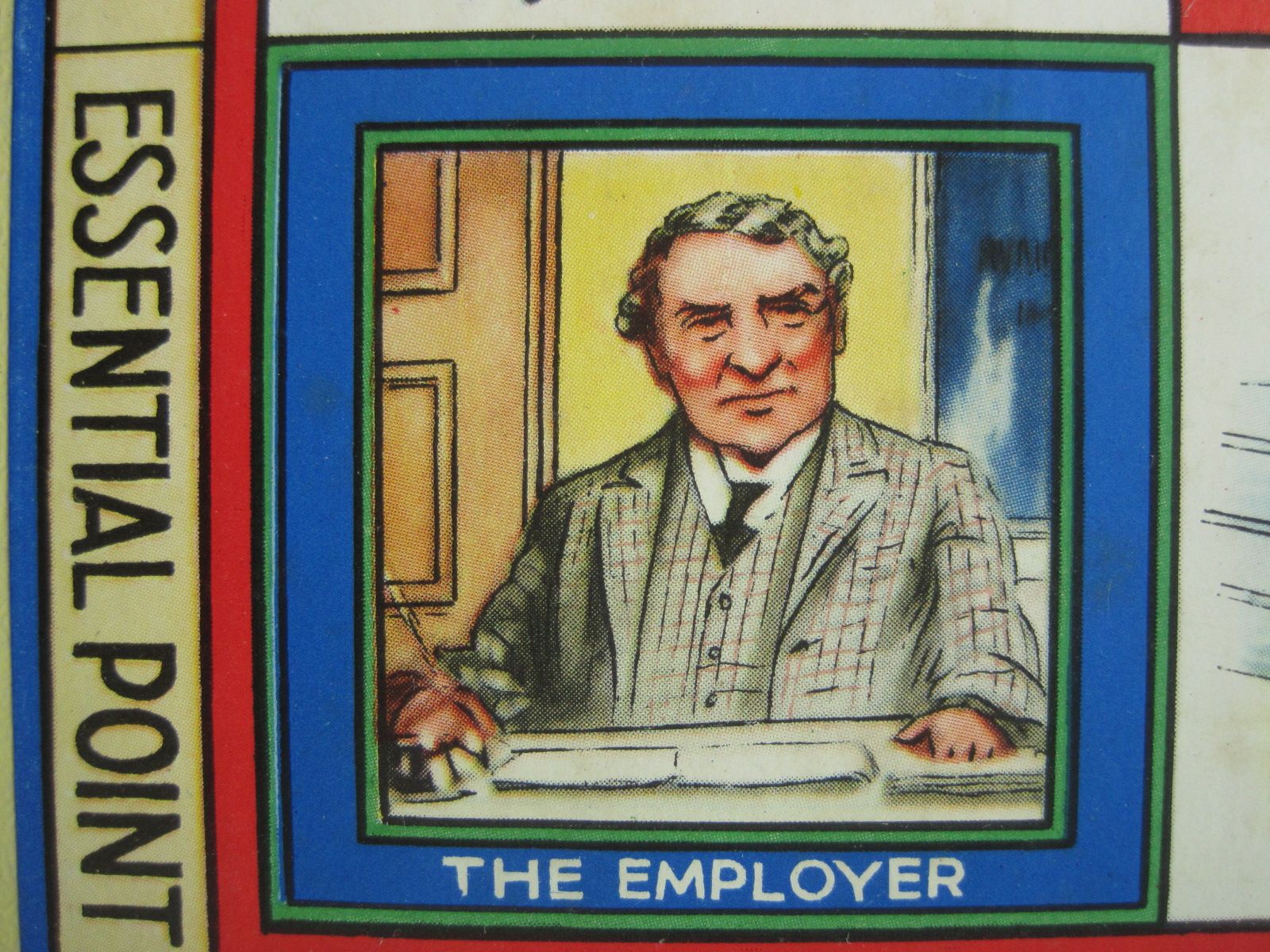

Removed from the historical context and considered critically, the game’s representation of society’s ideal may appear to us today as somewhat restricted. The instructions peddle the expected ‘norms’ of the day: ‘the object of the game is to join up with a partner, i.e. “to get married”’. Even at play, selected partners are to be ‘preferably of the opposite sex’. Representation of working women on the board and cards is restricted to just one example, the Mistress of the Dame School, while men sit on squares representing The Bank Manager, The Chancellor, The Doctor, The Chairman, The Clergyman and The Lawyer. The faces across the board are all white and middle class. Seen from today's perspective, the game is clearly not, and never really was, ‘for everyone’.

Items from our past, albeit now seemingly outdated, can be a valuable way of prompting us to look at what we would now regard as misconceptions and to reflect on whether we have come far enough to change them. However, at a time when many consider that society still has far to go, such items can also be encouraging, showing us that change, while maybe slow, is inevitable. Perhaps 50 years from now, people will be able to discern real changes put in train by the gathering momentum of today. This simple board game, now back in its box and on its way to display, has certainly made me think.

If you have enjoyed Culture on Call and you are able to make a donation, please click the link below. Any support you can give will help us keep communities connected to culture in these difficult times.