Following her new exhibition at City Space, Winchester Discovery Centre, Facing Both Ways: Walking the South Downs Way through Painting, Melanie answers our questions about contemporary landscape painting, her PhD research and interest in diverse ecological philosophies.

1. How did you first become interested in both the genre of landscape painting and natural observation?

Melanie: I first became interested in landscape painting in 2012, when I was invited to exhibit, along with three other Land2 members, in the exhibition Landscape, Art, and Uncertainty at Southampton City Art Gallery. The exhibition explored many of the themes identified in this exhibition, whilst at the same time responding to neo-romantic artists held in the galleries collection. I chose to respond to the painter Ivon Hitchens, who lived twenty-six miles from where I live.

I not only examined Hitchens paintings, but made pilgrimages to the places he painted, as well as researching his influences and approaches to painting. As a result I made a body of landscape paintings about the landscape in and around where I live, one of which is now on display at Winchester Registry Office.

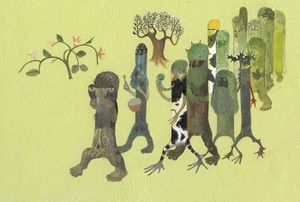

What I found intriguing about Hitchens paintings is the fact they are abstract investigations about place and yet are identified in the classic tradition of landscape painting, following the picturesque formula including, foreground, mid-ground and background, with often a path or water leading the eye through. Hitchens, having had formal art training, was able to combine abstraction, the picturesque and genius loci (spirit of place). Evolving this approach further, my aim is to eliminate picturesque structures or at least have multiple perspectives including my imagination as a way to reimagine the landscape.

2. Could you tell us a little bit more about your mission to “rewild” landscape? What does “rewilding” imply in the sense of looking at our surroundings and archiving our land?

Rewilding is a revolutionary ecological philosophy started in the UK by Charlie Burrell and Isabella Tree at the Knepp Castle estate on the border of the South Downs National Park. Initially there was outrage, as farmland and formal gardens were left to nature, but in so doing the results demonstrate extraordinary increases in wildlife.

The way we envisage landscape can be traced back to renaissance geometry found in paintings by Claude Lorrain whose influence on wealthy landowners in the seventeenth century contributed to the way estate land was set out as well as underpinning the concept of the picturesque.

Prior to the seventeenth century in the UK, the word landscape and landscape paintings did not exist. The introduction of both the word and paintings have influenced a disconnect, putting us always outside of what we are looking at.

3. You have very fascinating research which looks carefully at the landscape archive in different regional art collections, what feature of these collections particularly stood out to you?

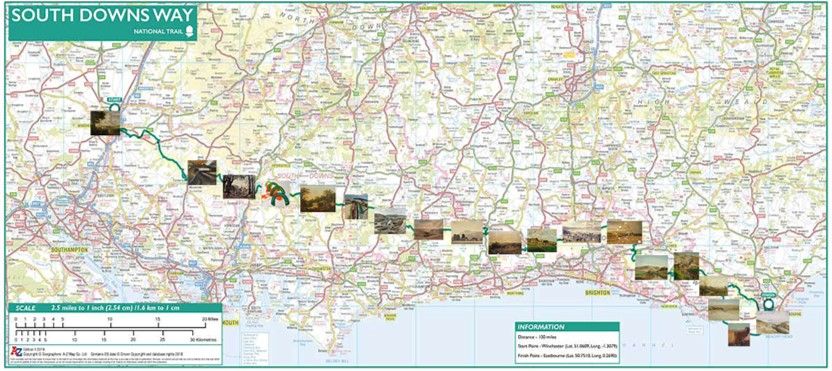

One of my methods of investigation is a database I made of paintings held in regional galleries featuring the landscape of the South Downs National Park from 1660 to the present day. After creating the database, I then isolated locations from the South Downs Way National Trail guidebook and matched each location to a historical painting. What I identified is that there are no paintings from the Hampshire/Sussex border until reaching Winchester. It could be concluded that by not having regional collections, local landscapes are not collected, as a result denying educational and research opportunities on a very broad level.

4. Do you have any particular favourite landscape painting which you believe gives us clues as to how the South Downs Way was perceived and thought of in the past?

My favourite paintings of the South Downs landscape are by, as previously mentioned Ivon Hitchens, but also Harold Mockford; especially the way he combines the chalk landscape with narratives and motifs including the moon. Eric Ravilious’ paintings again bring to the fore the geology of the landscape alongside the detritus of everyday living, but in a magical slightly ethereal way. Vanessa Bell, a founding member of the Bloomsbury group, produced post-impressionist paintings of the landscape, as did William Stott, who captured the Downs in liminal light, offering a romantic view of what were harsh times for farmers. Finally, J. M. W. Turner whose paintings are phenomenal, not only his paintings but the combination between his imagination and the landscape, forming aesthetic narratives that might be read as real, but are re-imagined.

5. What does your research point to in terms of the role and importance to re-envision the landscape of the South Downs Way?

Re-envisioning the South Downs landscape is important, especially at this pivotal point regarding the climate crisis. In so far that the more abundant and diverse species there is, including in the soil, rivers, and sea, the healthier the landscape and ultimately us, but to do this, areas of rewilding must take place as well as the reintroduction of certain species. By accepting that the landscape is not pretty or neat and tidy, as well as allowing the natural decay of living organisms along with open access for walkers will encourage, through education, a new way of seeing and being in the landscape.

Visit Facing Both Ways: Walking the South Downs Way through Painting, open until 11 September 2021 at City Space, Winchester Discovery Centre. All the works on display are for sale and available to collect at the end of the exhibition. Entrance is free and there’s no need to pre-book your visit.

Follow City Space and The Gallery on Instagram.