Allen Gallery volunteer Jackie takes us through the history of the beloved sweet treat this National Cake Day...

The ancient Egyptians are thought to have created the earliest versions of cake and often made honey-sweetened dessert breads. The word ‘cake’ itself is of Viking origin, from the Old Norse word "kaka". The ancient Greeks called cake πλακοῦς (plakous), which was derived from the word for "flat”. It was baked using flour mixed with eggs, milk, nuts and honey. The Greeks also had an early form of cheesecake, while the Romans developed versions of fruitcakes with raisins, nuts and other fruits.

The first written evidence of “cake” dates from the 1300s. The term seems to refer most specifically to forms of bread that are enriched and flat, with flatness being the distinguishing characteristic. One early definition is given by John de Trevissa in 1398, where the crucial feature distinguishing cake from bread seems to be that it is turned over during baking and is therefore flat on both sides; “Some brede is bake and tornyd and wende at fyre and is callyd …. a cake”.

Sponge cakes, leavened with beaten eggs, originated during the Renaissance. In mid-17th century Europe, cakes were frequently baked as a result of advances in technology and access to ingredients. Europe is credited with the invention of modern cakes, which were round and topped with icing. The first icing was usually a boiled mixture of sugar, egg whites and flavourings. Originally the cake was returned with icing to the oven and baked until hard and glossy. Many cakes contained dried fruits, like currants and citrus.

It wasn’t until the 19th century and the invention of baking powder that what we think of as conventional cakes were first detailed in recipes. The treat was considered a luxury, as sweet ingredients, such as sugar and chocolate, were very expensive. During this time, cakes were baked with extra refined white flour and baking powder instead of yeast. Buttercream frostings also began replacing traditionally boiled icings. Cakes were usually baked for special occasions, as they were made with the finest and most expensive ingredients available. The wealthier you were, the more likely you were to consume cake often.

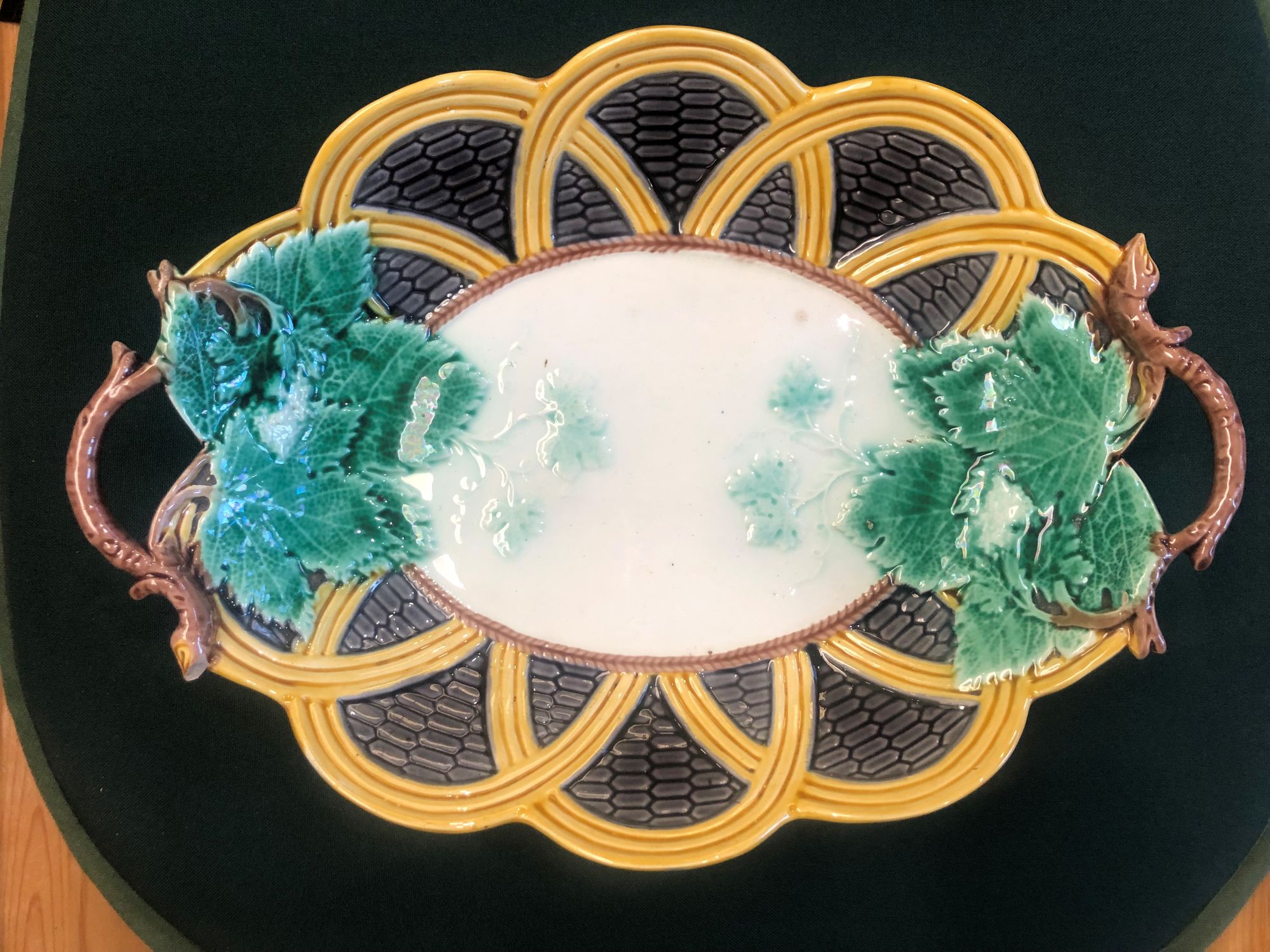

Due to the advancements in temperature-controlled ovens, a baker’s life became much easier. No longer did bakers have to continually watch and wait for the cake to bake. Ingredients became more readily available, and cheaper, so more people could bake them, or even buy them in shops. Although cakes can be baked in virtually any shape, there are several theories as to why most cakes are traditionally round. Generally, round cakes were made by hand and moulded into round balls. While baking, the bread naturally relaxed into rounded shapes.

There is another theory, which is that gods prefer round cakes. In ancient times, some civilizations baked cakes as a generous gesture for their gods and spirits. A round cake was meant to symbolize the cyclical nature of life, as well as the sun and the moon.

Access to ingredients made a big difference to family bakers in the 1930s and 1940s. When Britain entered World War II, commercial bakers were an important part of domestic life, but as the war continued, the baker was to become a vital lifeline for the home front. When news of the war broke, Britain was importing around 20 million tons of food each year. However, importing food to keep the country fed became problematic as cargo ships were needed to carry troops and munitions. Rationing had to be introduced, which spelled many changes for home and commercial bakers alike. The Ministry of Food advised housewives to try using mashed potatoes in place of flour, and carrots as a sweetening agent, leading to some curious cake recipes, such as potato shortcake.

Baked bread consumption was at a consistently high level in the 1940s and while bread and flour were not rationed, white flour was in short supply and went to commercial bakers. Bread was considered a vital resource and the British Ministry of Food urged citizens to “make the most of every crumb”. Posters urged householders to be economic with their bread consumption, through slogans such as ‘Save the Wheat and Help the Fleet’, and 'The Kitchen is the Key to Victory: Eat Less Bread’. The shortages of fat, sugar and white flour naturally changed the goods baked and sold commercially. Cakes returned to being stodgier, plainer affairs, with bread pudding, dripping cakes and lower-sugar cakes replacing pre-war delicacies.

Rationing was so tight that wartime wedding cakes were sometimes made from cardboard and for display only. Bakers would loan the cardboard cakes to wartime sweethearts, so it looked as though they had a cake in their wedding photographs. Severe sugar rationing meant that being able to pipe cakes with royal icing was a rarity, even among master bakers, and their apprentices were often given mashed potato in a piping bag to keep piping skills honed. The baking of wedding cakes became a community effort. With rationing in full swing, it was common for each wedding guest to be asked to donate an ingredient for the wedding cake and the local baker to mix and bake the cake.