In this article, Visual Arts Exhibitions Assistant, John Reed, spoke to Kathleen Palmer, guest curator of the exhibition Beyond the Bonnets, open at The Arc, Winchester, until 2 November. Kathleen gives brilliant insights into her work on this show and reveals which stories and objects moved her the most. The exhibition evidences the lives of working regency women and provides a rich new way to engage with Jane Austen in the 250th year since her birth. Fact and fiction were balanced in a novel curatorial approach. Kathleen was recruited as part of a wider project to undertake research for and shape the show.

What sparked your interest in taking on the Beyond the Bonnets exhibition project, was it the chance to work on a Jane Austen related show, or the specific angle of the brief?

It was both! I am a devoted reader of Austen’s novels. I was given a copy of Pride and Prejudice as a young teenager, and I was hooked from then on. Over the years I have read all of the published novels, and I’ve returned to my favourites many times. I enjoy the author’s voice, which is so dry and funny, her acute observation of human nature, the journeys of self-discovery and the love that her main characters make. Beyond the Bonnets was taking a new and interesting angle on Austen which led on very naturally from work that I had done as Curator at the Foundling Museum. The story of the Foundling Hospital includes the lives of ordinary working women who, as the best of the limited options open to them, gave up their babies into the charity’s care. In 2018, I curated a special exhibition there, Ladies of Quality & Distinction, which explored the role of women in setting up and running the Foundling Hospital. I learned a lot about working women, from school mistresses to cooks and wet nurses to laundry maids, which helped me enormously with Beyond the Bonnets.

How did you approach the sources at your disposal, and how did you get the balance right between fact and fiction?

As part of the Austen 250 celebrations, the exhibition had to start with Austen and her much-loved novels for the dedicated fans of Austen, who might come from far and wide. It also needed to resonate with the Trust’s local audience, who wanted to connect with stories of Hampshire’s history and people as well as celebrate its most famous daughter. I curated the exhibition to combine three different strands: quotes from the novels describing working women, extracts from Austen’s letters mentioning real-life working women that she knew, and documents from the Hampshire Record Office which told the stories of local women whose lives paralleled those of Austen’s characters and who worked in the same roles. These strands of fiction and fact are woven together throughout the exhibition. A relevant quote from one of the novels introduces each of the working roles, and further fictional extracts illuminate and enliven individual objects. Factual information includes explanations of the nature of the work and the tools, extracts from letters or other contemporary sources, and often a biography, the life story of an individual real woman employed in that job. I hope this strikes the right balance for all kinds of visitors.

Which object and story that you came across in undertaking research for this exhibition most resonated with you?

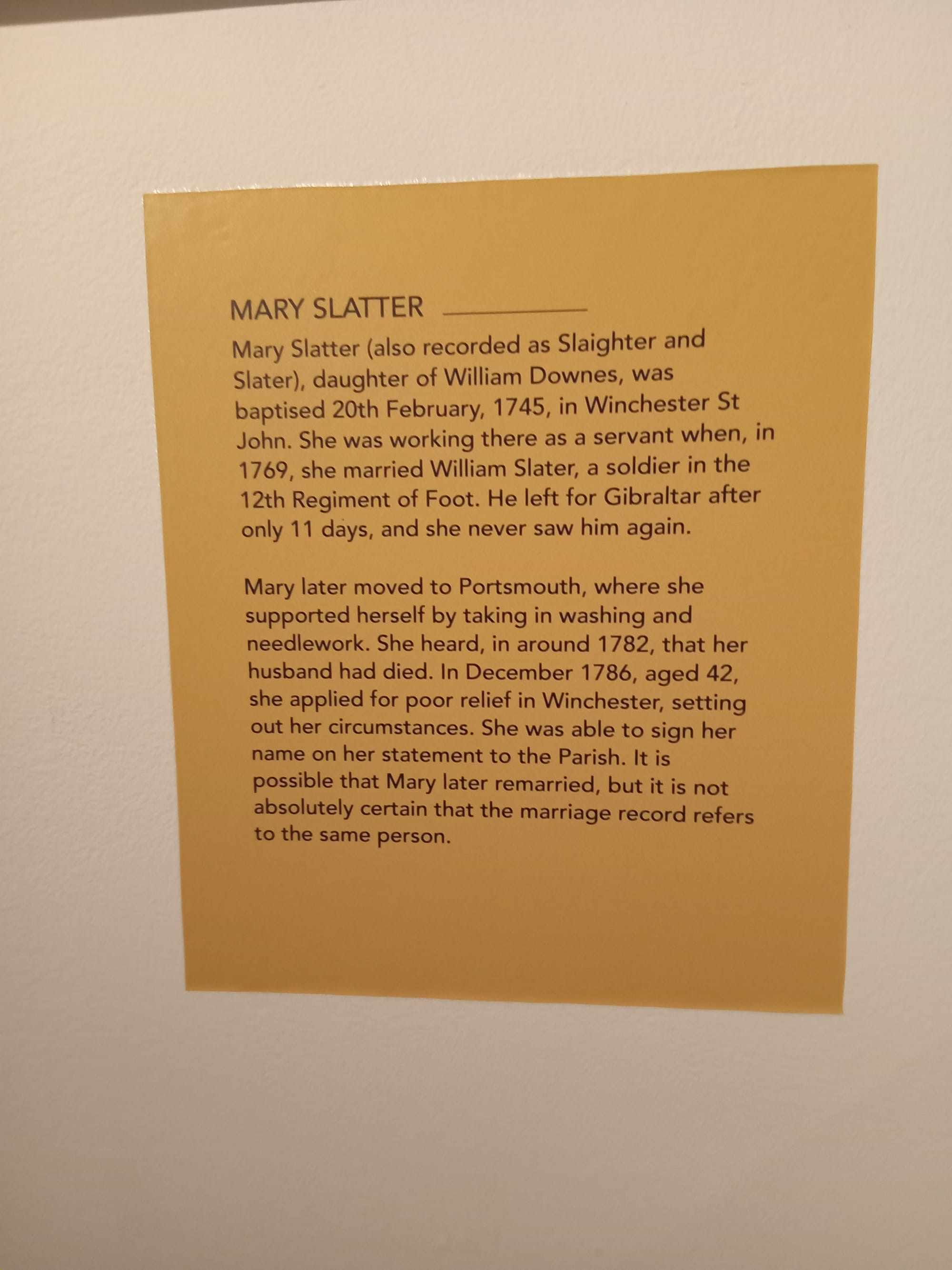

It’s extraordinarily difficult to single out one story from amongst the women whose lives were uncovered by the project’s wonderful research volunteers. So many of them made their way in life and faced difficult times with great resilience, at a time when women had limited rights and opportunities. There were several long-lived, redoubtable women like draper and librarian Mrs Mary Martin, and housekeeper Mary Mountford where our research revealed quite complete life stories. Others were more fragmentary, but were tantalisingly close to being first-hand accounts. I was especially touched by the story of Mary Slatter, who married a soldier, and spent just 11 days with her new husband before he was posted abroad, never to return. Mary managed to make a sketchy living for many years as a washerwoman and taking in sewing. She finally applied for poor relief from her parish, and her story was recorded by the administrators. The tiny coins and account book on display help to illustrate the very small amounts that women earned for such laborious, unpleasant work. One object which resonated with me very personally was the teething ring. My own baby had a very similar little ring, with a tiny rattling ball attached, and so it struck me immediately as familiar. Sometimes objects just seem to connect right across time, for all kinds of different reasons.

Do you feel that the exhibition will have a lasting legacy?

I hope that it will, and in a range of different ways. I like to think that the many visitors to the exhibition will have found connections with the past, and taken away new insights into Austen and her world. The exhibition has involved local volunteer researchers and advisors as part of a wider project exploring new ways of making exhibitions and using collections, and this will feed into the way Hampshire Cultural Trust works in the future. Together we have uncovered stories about local working women and found out more about objects in the collection, both of which will support future exhibitions. For instance, the life story of Mary Martin is likely to feature in a display at the Willis Museum soon. I’m also writing about the exhibition for an online academic journal focused on Jane Austen, and so the research and approach will feed back into the scholarly community too. I still find it striking to go into a gallery or museum and to visit an exhibition like this one which is completely centred on the experiences of women. I am so pleased to have played a part in celebrating not only Jane Austen, but also the ordinary working women in her world.

The exhibition runs at The Arc, Winchester until 2 November. In November, the exhibition will tour to the Willis Museum in Basingstoke where it will be open from 12 November to 22 February.