21 works of graphite, charcoal ink and watercolour translated into photogravure prints make up the exhibition Georgia O’Keeffe: Memories of Drawings. Produced in the mid 20th century the contents of this show are the results of a collaboration between Georgia O’Keeffe and printmaker Doris Bry. In this article we ask, why photogravure?

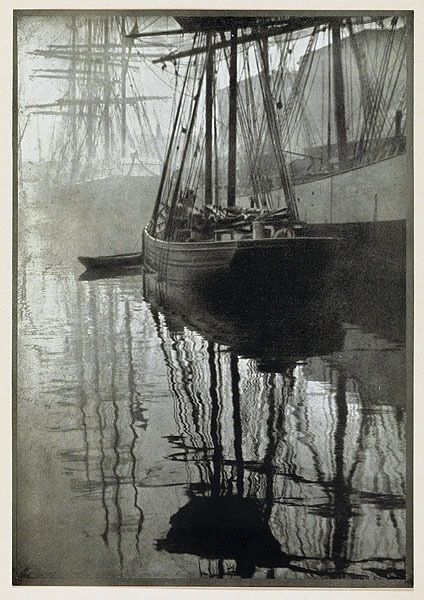

The production of photogravure prints viewed through the eyes of the modern-day layperson and printmaker alike appears eccentric and excessive. Watching a video of the process performed by modern experts presents a sensory overload of excruciating detail. Stage after stage provokes a torrent of fickle variables. Moreover, attaining control is expensive and painstakingly laborious. Precious plates, films, inks and papers accompany multiple rounds of carefully coordinated development, exposure and etching. Speaking on the creation of his photogravures, photography impresario Coburn (1882-1966) stated that ‘no one will ever know save those who have experienced it, what such an undertaking involves’. Photogravure was not for the faint of heart.

Despite these drawbacks, artists including O’Keeffe, Bry and Coburn continued to employ such an unforgiving method of reproduction. But why?

Historical significance

The answer to this question is grounded in the history of photography as an art form and method of information transference. Photography invented in the 19th century allowed images to be captured and distributed as half-tone prints. Critics in photography journals such as The Crayon (1851-1861) scorned the technology, stating that it lacked ‘something beyond mere mechanism at the bottom of it’.

The photogravure process was the first process to produce photographic prints with continuous tonal value in photography. Its adaptability made it exceptional for generating the expression and careful delineation that artists required to make explicit the subjectivity and profoundness of photography.

Photogravure and avant-gardism

Photographers, including Stieglitz, Coburn and Steichen, realised the potential of gravures through their ground-breaking works. These photographers were O’Keeffe’s avant-garde allies in adversity, and together, they leveraged the learnings of the old and the new to overcome their respective barriers.

Created at a time of increasing interconnectivity, mechanisation and cross-pollination of ideas and methods, Photogravure enabled artists, including Stieglitz, to distribute images of work internationally. These reproductions allowed students and connoisseurs to observe international excellence in its full glory.

Advertisements of books of gravure prints in newspapers and journals such as the Critic (1868-1896) and the Atheneum (1828-1921) accrued a plentitude of adjective plaudits proclaiming photogravure prints beautiful, exquisite and sumptuous.

Arthur Dow, who majorly influenced O’Keeffe, was a proponent of beauty in art and saw the value of gravures. In fact, in Dow’s didactic book, Composition, he advises students to copy from gravures of Japanese art and states that ‘Good photogravures may now be obtained’ if one cannot see the original.

Through photogravure, O'Keeffe would have first seen works that informed her use of pictorial space, line and tone. High-quality photogravure books, including The Pictorial Arts of Japan by William Anderson, were published in 1886 and sold internationally. O’Keeffe had access to the finest works from the Ukiyo-e school, including the prints of Hokusai, famed for the Great Wave, because of high-quality printmaking technology.

These Japanese artworks added to the rich source material that O'Keeffe had to draw upon, including the works of Matisse, Picasso, Cezanne, and the whole western canon of modernist art exhibited at Stieglitz’s 291 gallery. The reproduction and manipulation of photography were essential to the unique and innovative synthesis of styles that set O’Keeffe at the forefront of the American avant-garde.

A reciprocal act

O’Keeffe was part of a vibrant and dynamic early modernist American movement that propagated the spread of cutting-edge art, technique and design but not at the expense of qualitative artistic processes. It is unsurprising then that O’Keeffe utilized the medium of photogravure to preserve her drawings and ensure they remain in public circulation and spark the imaginations of enterprising artists for years to come.

More information can be found out about photogravure in the additional information provided in the exhibition, open until the 15 November at The Gallery, The Arc, Winchester. Click here for more information.