Part six of a nine part series of articles from Mark Barden, our Community Cultural Experience Manager here at Hampshire Cultural Trust, 'digging the dirt' on all things archaeology.

Episode 6: The appliance of science

Exposing artefacts during excavation can result in rapid and irreversible damage and it’s the role of the conservator to stabilize, clean and preserve this material to prevent, or at least slow down, further deterioration whilst keeping intervention to a minimum.

Organic material, e.g. textiles, wood, leather, when periodically exposed to moisture, can rapidly decompose. Organic materials survive best in hot, dry environments, such as deserts, or in waterlogged, colder conditions with constant temperatures and low oxygen levels.

Waterlogged wood can be conserved by replacing the water with materials such as Polyethylene glycol (PEG), timbers can then be stored dry, making them easier to study or display. The method used to preserve the timbers of the Mary Rose.

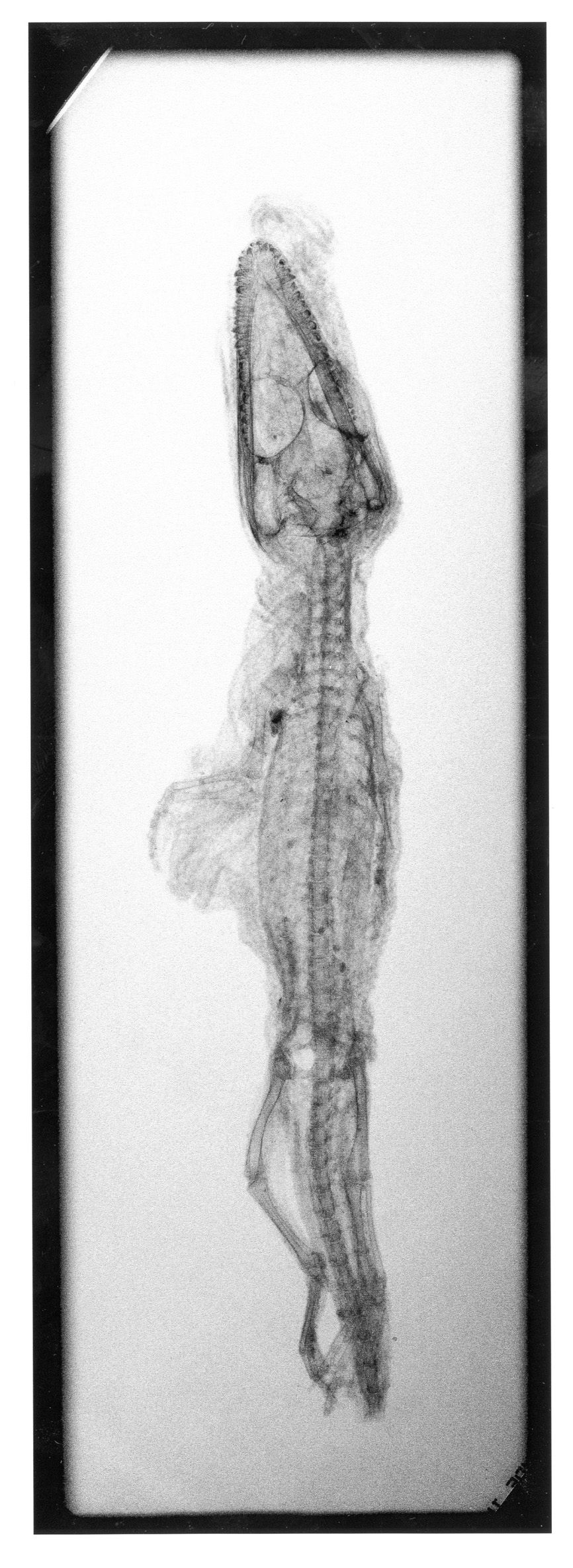

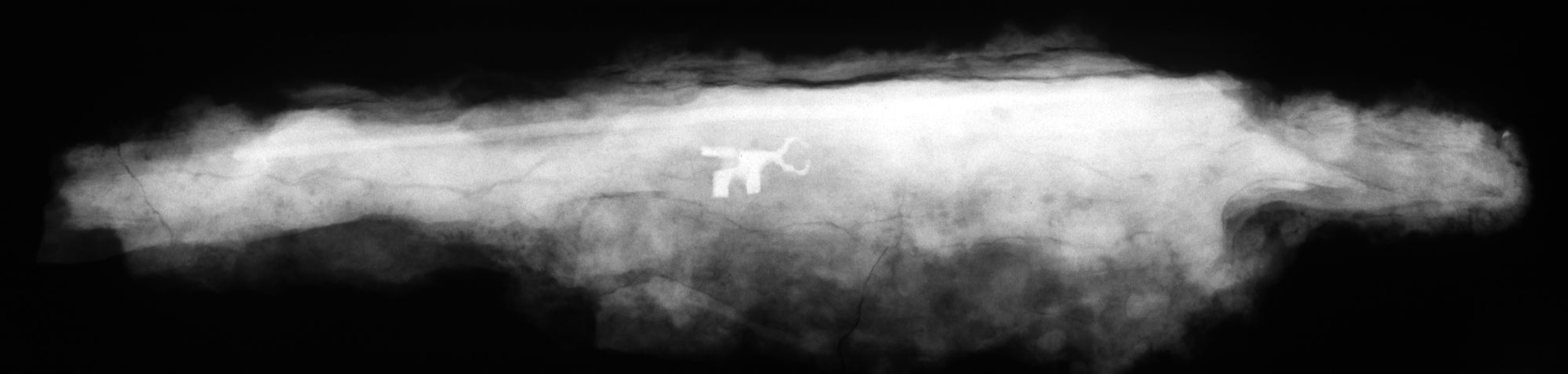

Metal can be a challenging material to conserve with iron particularly prone to decay. Iron oxide corrosion can completely obscure the surface of an object, in some cases making it almost impossible to identify. X-rays can tell the conservator how much of the original object survives and reveal hidden details.

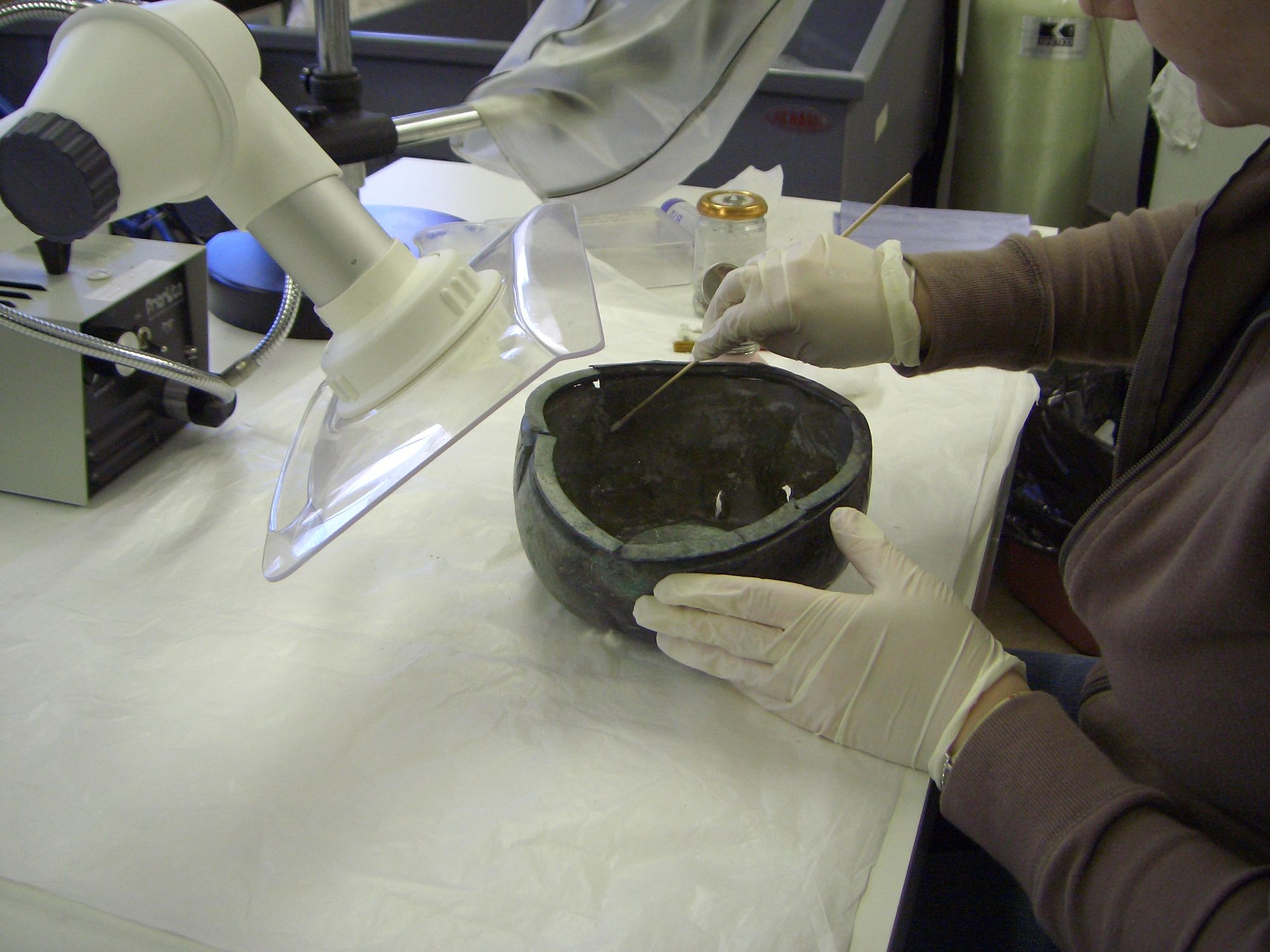

“Bronze disease” is a progressive deterioration of copper alloys that may lie dormant until the object is exposed to moisture and oxygen, creating physical stress in the metal resulting in cracking and fragmentation. Chemical corrosion inhibitors can be used to halt the “disease” but this is usually only a temporary solution and regular monitoring and further treatment is often required.

One of the most significant applications of science in archaeology has been the development of various techniques of dating human activity in the past.

Radiocarbon Dating is probably the most familiar and is used for dating organic remains based on the fact that all living things absorb Carbon 14 (C14) which then begins to decay, at a known rate, at the moment of death. The missing amount of C14 in a sample can be measured to provide a date range.

Thermoluminescense dating relies on the fact that all inorganic material, such as the clay we make pots out of, absorbs radiation at a constant rate, accumulating and trapping electrons uniformly over time, a rate that can be measured. When we make a pot out of this clay, and fire it in a kiln, the heat resets the electron count to zero and the accumulation process begins all over again. We now know when the pot was made.

If you have enjoyed Culture on Call and you are able to make a donation, any support you can give will help us keep people connected.