The penultimate installment of our Festival of Archaeology series on Culture on Call sees Cultural Experience Manager Mark Barden discussing what we can learn from human burials when organic remains are no longer present.

Human remains provide us with our most detailed and intimate stories about individuals and populations of the past. Carbon and Isotope analyses of tooth enamel can tell us about diet and environment. Skeletal remains can tell us the age and sex of an individual, as well as revealing disease, injury, lifestyle and often the cause of death. DNA allows us to discover how individuals are related to each other, and to us. With advances in scientific techniques, human remains excavated decades ago continue to reveal their secrets.

The type of soil the individual is buried in is key to the survival of the remains. Burial in very dry or wet conditions can result in amazing discoveries, such as the Peruvian mummies and Irish peat bodies.

At the other extreme, very acidic soils can destroy all organic remains. Archaeologists then primarily rely on survival of objects, such as ceramics and metalwork, to date the burial and help determine the sex of the individual.

Probably the most famous burial ‘without a body’ is the Sutton Hoo ship burial. Excavated in the 1930s, it was one of the richest archaeological finds ever discovered in Britain. Not even the huge ship timbers survived, replaced by beams of dark sand - a ghostly outline, concealing the amazing treasures that lay hidden in the vanished burial chamber at the heart of the ship.

The Bargate Burials

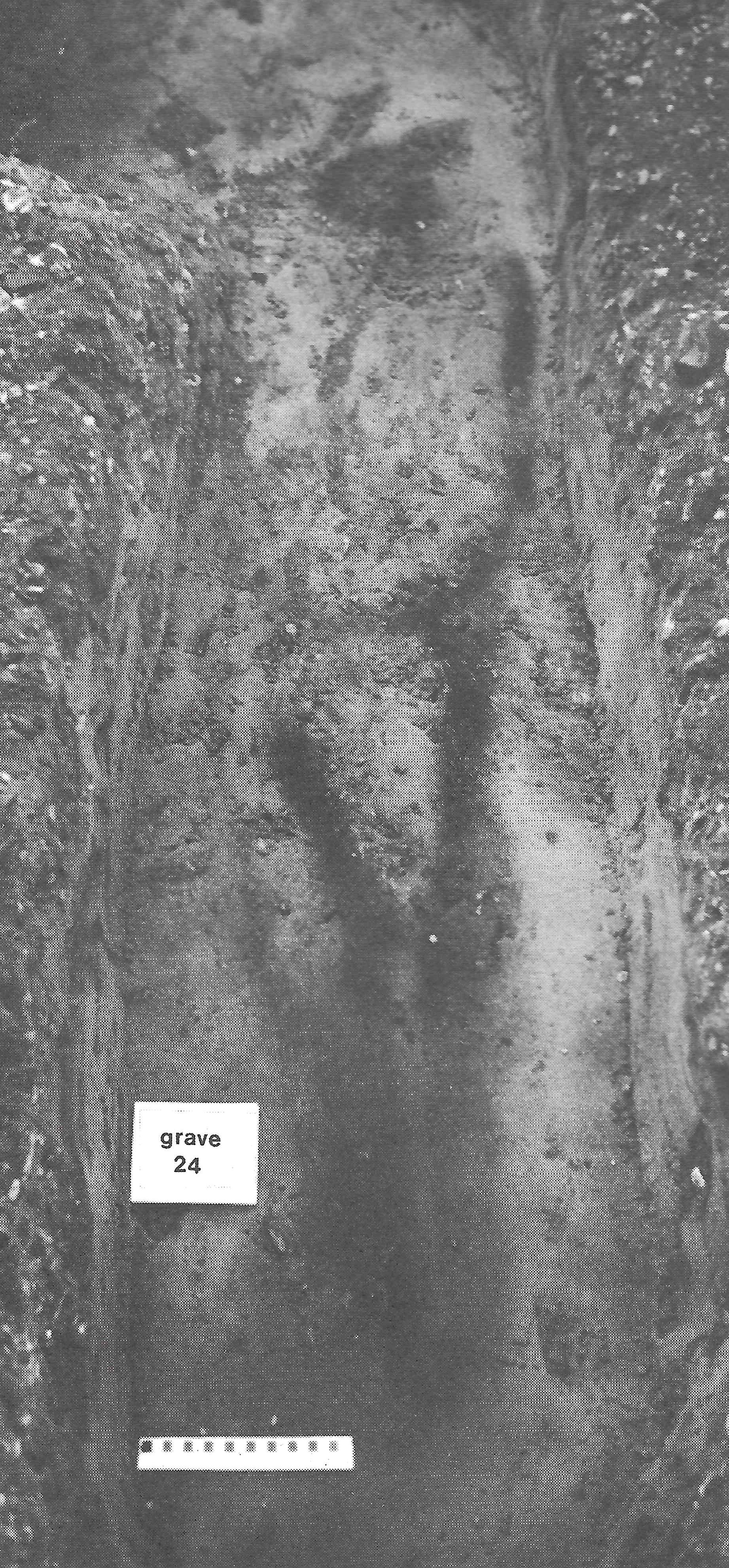

The first Saxon settlers arrived in what was to become Christchurch in the late 500s AD and we got to meet them in 1978, when over thirty burials and four cremations were excavated on the site of the towns Bargate.

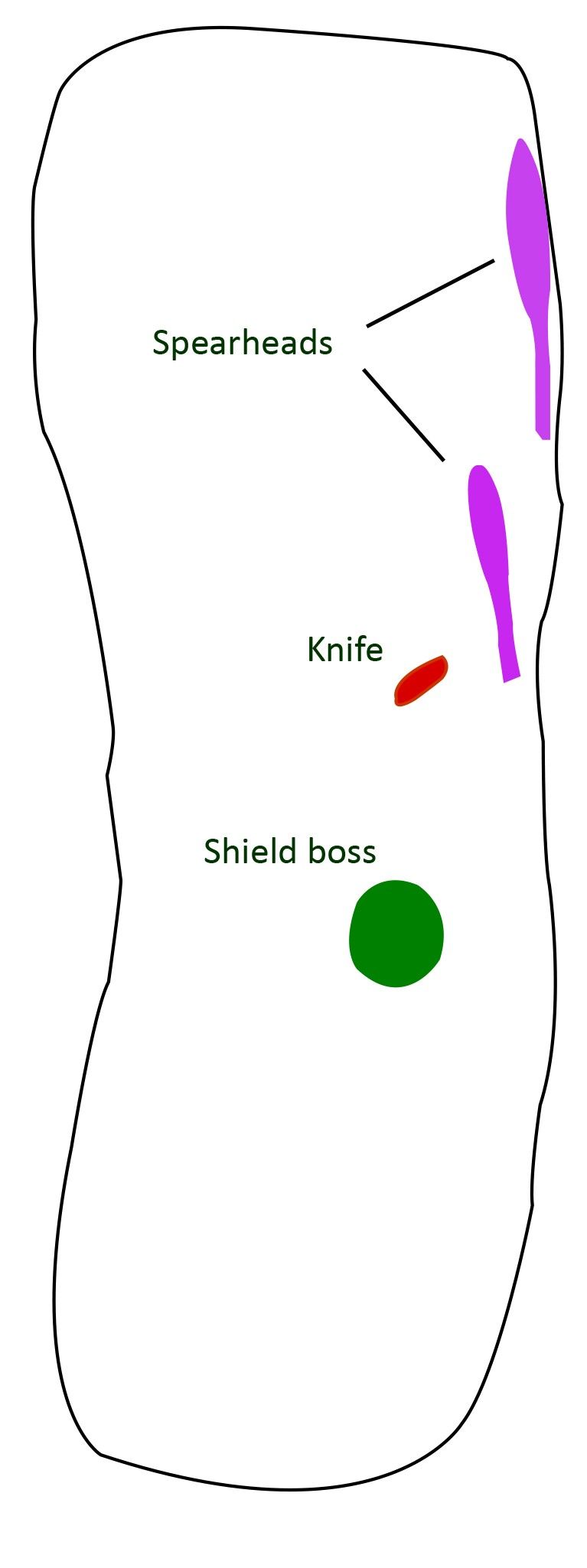

Because of the acidic soil, none of the graves contained bones, only ‘body stains’- ghostly outlines in the soil. Almost all the organic material, bones, textiles and wood, had perished. Only the metalwork survived, allowing archaeologists to date the burials to the 6th and 7th centuries.

Eleven of the graves contained iron weapons and remains of shields and spears, and others included knives and buckles. Without the human remains it proved difficult to tell male from female, old from young. Some small fragments of organic material survived where textiles and wood had been in contact with the iron.

We have yet to find the village these people called home, but a clue may be found in the original Saxon name for Christchurch; Tweoxneam, Old English for ‘between rivers’, a reference to the Avon and the Stour. Perhaps one day a chance discovery or stray find may lead us there.

If you have enjoyed Culture on Call and you are able to make a donation, please click the link below. Any support you can give will help us keep communities connected to culture in these difficult times.