In November 2022, Hampshire Cultural Trust opened a brand new visitor attraction in Winchester: 878 AD.

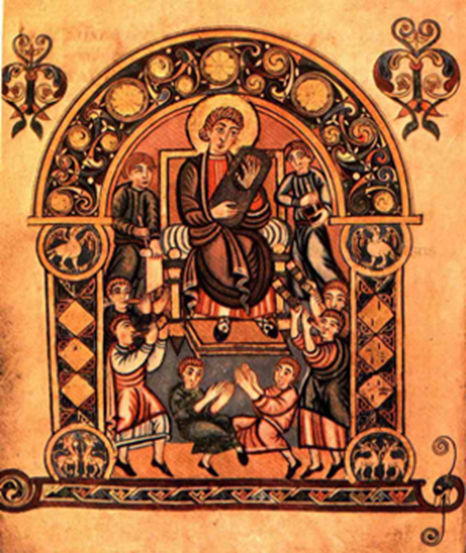

Helping us tell the story of Anglo-Saxon Winchester, Dr Lucy-Anne Taylor acted as special adviser on Anglo-Saxon sounds and music for the project. Below, she shares a little more of her research.

Music and sound are constantly present in the world around us, as they were in Anglo-Saxon times. As armies left for battle, fought and returned, they heard the sound of the horn[1].

Epic poems, including Beowulf and Elene, describe the horn being played in battle, drunk from during feasts and used to decorate people’s homes. According to Beowulf, the horn sounded eager and brought relief to those who heard it. Anglo-Saxons may have rallied around the sound of the horn, especially the soldiers in battle, making it vital to warfare of the day. In this epic, the horn’s sound drives away the sea creatures, keeping the people safe from such monsters.

Two of the Exeter Riddles (written in the 10th century by an unknown author) describe the treasured nature of the horn, and that both men and women used them – even if in different circumstances. Its role as a sounding device, particularly during battles both at sea and on land, is the most prominent feature of the riddles, but the use as a drinking horn is also hinted at.

Unless a person blew a horn or called out when leaving the highway, according to the Lawcodes of King Wihtred of Kent (AD 695), they were assumed to be a wrongdoer. The horn was used to keep people safe and to uphold the law. People would have been used to, and probably glad of, the sound of the horn, at least in the Kingdoms of Anglo-Saxon England where such law was enforced.

The people in Anglo-Saxon England could have made horns from several different animals, including cattle, sheep and goats with the larger horns being more important. The biggest horns came from Aurochs. These may have been imported or possibly survived from previous centuries as the aurochs only survived on the continent in Anglo-Saxon times. They were therefore only available to the wealthiest. Some horns had metal bands for decoration while others were plain.

What the Anglo-Saxon people played on the horns is unknown and there are few descriptions of its sound. In the later Middle Ages, horns produced different pitches, and also rhythms, for hunting horn signals. Maybe, they were adapted for melodic entertainment, too. What we do know is that the people would have heard the horn in battles, such as those of 878 AD!

You can hear what some of these instruments sounded like by visiting the following YouTube channel and clicking on the videos, listed here.

[1]Horns and trumpets were not necessarily differentiated in the same way as they are today; when referring to the horn, it should be recognised that an instrument under the name of trumpet may also have been meant.