Behind the scenes of the conservation work that goes into crafting our exhibition displays.

Every so often, I get the opportunity to work on an object that not only is beautiful and historically significant, but resonates with me personally, and offers me the chance to get really creative with my treatments and repairs. When I’m not being a conservator, I am a musician, and have a particular love for musical instruments of all kinds. When this mandolin was proposed for this year’s Jane Austen exhibitions I was delighted to get the chance to commune with it!

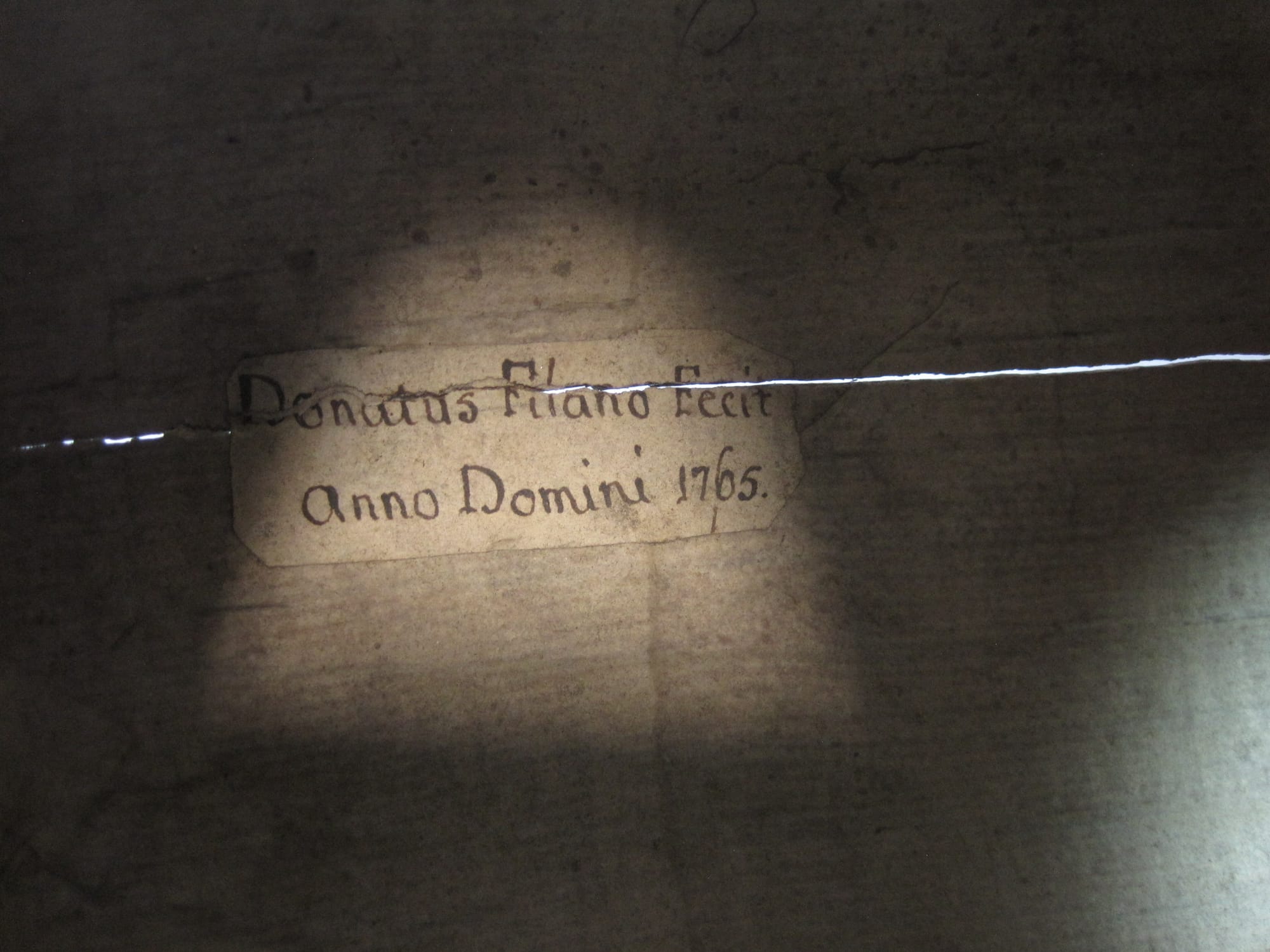

The mandolin is from Naples in Italy, and was made by the well-known maker Donatus Filato in 1765. The body is likely rosewood, with frets of a darker wood which may be ebony. There are thin strips and panels all over the instrument, both decorative and functional, of mother of pearl, tortoiseshell, bone and ivory. A line of ivory pegs at the bottom of the teardrop-shaped body is intended hold the strings (which would originally have been gut) in place, while at the other end wooden pegs are for tuning. This instrument should have had eight strings arranged in pairs and eight wooden tuning pegs, but four pegs are missing. Over its long life there have been several modifications – with at least one replacement peg, resizing of some of the peg holes, one peg inserted in the front instead of the back, and a modern metal-wrapped acoustic guitar string being the only string left. The bridge, which holds the strings up and away from the body of the instrument and allows them to vibrate freely when plucked, is also missing. Just visible on the inside of the instrument, excitingly, is a handwritten paper label stating the maker and date.

The instrument is likely to have been in the same condition since acquired - there are no records of any conservation work undertaken, or prior exhibition. On arrival into the lab it had a thick layer of dust and grease from repeated handling, dulling the varnish and the beautiful inlays. Structurally there were several issues, not least a 2.3mm wide crack running along the back, and seams that were opening up around the sides. The bridge was missing, and several pieces of mother of pearl, ivory and bone inlay were lost from all across the body, neck and headstock.

After assessing the mandolin and its condition, the next part of the process brings ethics and judgement in to play. As conservators, our mission is to preserve what exists, as it is, for as long as we can without causing further damage. This is really where conservation differs from commercial restoration, as the ethics for a museum object are necessarily different from somebody’s prized display piece, or something intended for continued use. However, in cases where museum objects are required for display, we must also consider aesthetic appeal, and more importantly how we can enhance the interpretation and accessibility of an object. Not in the sense of physical access, but in terms of understanding, connection to, and perceived relevance of that object to an individual – what it would have looked like, how it was used and how it worked. I had in front of me a sorry looking, grubby mandolin with half of it missing. Something had to be done, but in returning its beauty and allowing people to understand it, I had to tread as lightly as possible. Luckily this sort of problem solving is the part of the job I enjoy the most!

As the object was structurally damaged, the first step after a good clean was simply to repair the splits to the wood with conservation adhesive and clamping. After that, I was essentially window dressing – finding quick, reversible, sustainable and effective ways of creating the effect I wanted to make the object visually ‘whole’.

Conservation ethics state that in our work we must never replace any element that we do not know, or have sufficient evidence, was there in the first place. This is to retain integrity and honesty in the history and nature of the object – it is not for us to change their nature and future interpretation on imagination alone. This can be a difficulty when you need to put something back – but don’t know quite what. Researching parallel examples and looking for evidence on the object itself help a great deal, and can provide the evidence we need to proceed. In this case, photographs online of very similar instruments by the same maker were able to tell me what the missing bridge probably looked like, and marks in the varnish even showed me the location. Armed with the required evidence to justify my decision, I was able to make a false bridge from black Plastazote foam and acid free mountboard to fit, and created spaced slits in the false bridge to carry the strings.

While the bridge was a functional necessity, and showed how the mandolin worked, other replacements were primarily to enhance understanding of the mandolin’s decorative appeal and the skill of the manufacturer. With so much inlay missing, the overall look of the instrument had been lost. It was important to give the audience a full appreciation of its ornamental effect, without the eye being distracted by gaps and losses.

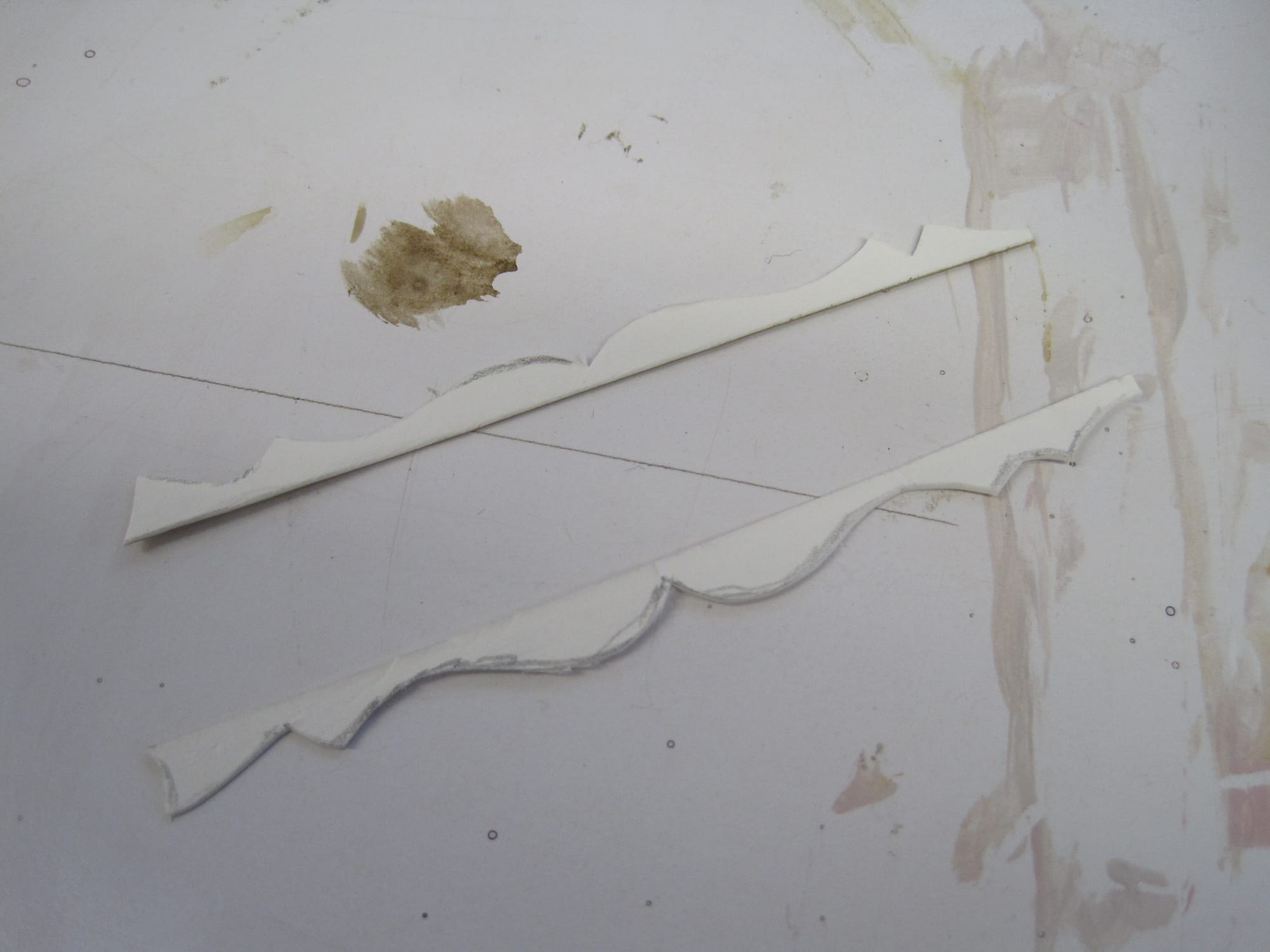

Replica inlays were cut by hand from acid free mount board, based on templates made from existing parts, or on traced outlines using light shining through. These were painted with built up layers of acrylic to mimic mother of pearl and ivory/bone. As the fake inlays were light and not structurally important, they could be tacked in place with a very small amount of easily reversible conservation grade adhesive. A replacement thin, black fret cut from a thin strip of acid free mountboard was also attached, coloured simply with black archival ink. Acid-free cardboard inlays – the height of cheap and cheerful!

Once all the inlay was present and the bridge in place, re-stringing was necessary – not only to complete the visuals of the instrument, but also to hold the bridge in place. Bridges on stringed instruments are never stuck on – possibly the reason why the original had been lost! So, the next problem to solve was what to use as ‘strings’. Real mandolin strings couldn’t be used as the tension would be far too great – but real strings don’t need to be used for an instrument that is never going to be played. Nylon fishing line was considered, but wouldn’t give the right look, and would probably still require too great a tension to keep it straight. In the end, raw cotton rigging thread – a buff colour and slightly rough, was chosen. Using the original ivory pegs at the bottom of the instrument, the threads kept beautifully straight when fed over the foam bridge and up to the pegs. Just one turn was enough to hold them with very light tension, making sure not to push the pegs in fully and risk getting them stuck should humidity rise and the wood swell. Four pegs were still missing, so something needed to be made to hold those strings in the holes, without damaging anything or causing stress. Back to the Plastazote foam, to carve wedges that the strings could just be tucked behind and held. Just enough tautness to give the appearance of strings, but without any tension at all.

So that was it – the mandolin completed, and with the addition of a bespoke stand made from heat-bended Perspex, it was ready for its moment in the spotlight. We have a 6 foot 6 inch rule in conservation – your work must be detectable for reasons of honesty and integrity, but if someone can stand just a few feet away and not realise the extent of the work you have undertaken, that’s the goal. We want the object to be appreciated for what it is – not for what has been added - but I hope this peek behind the scenes has opened up a little of what we do and why we do it!